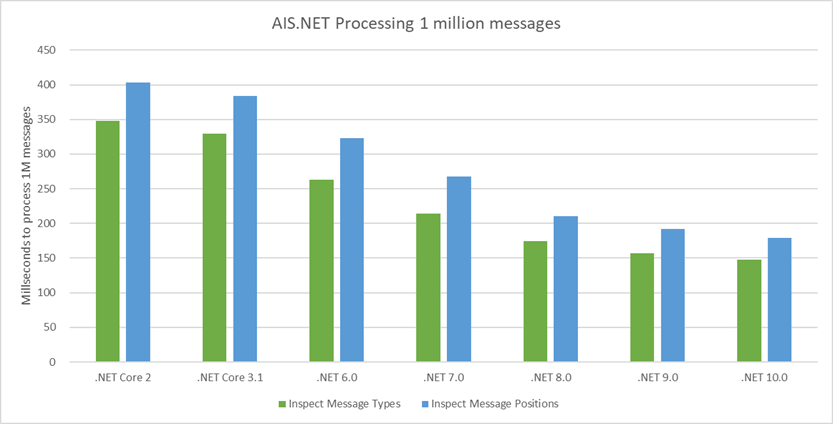

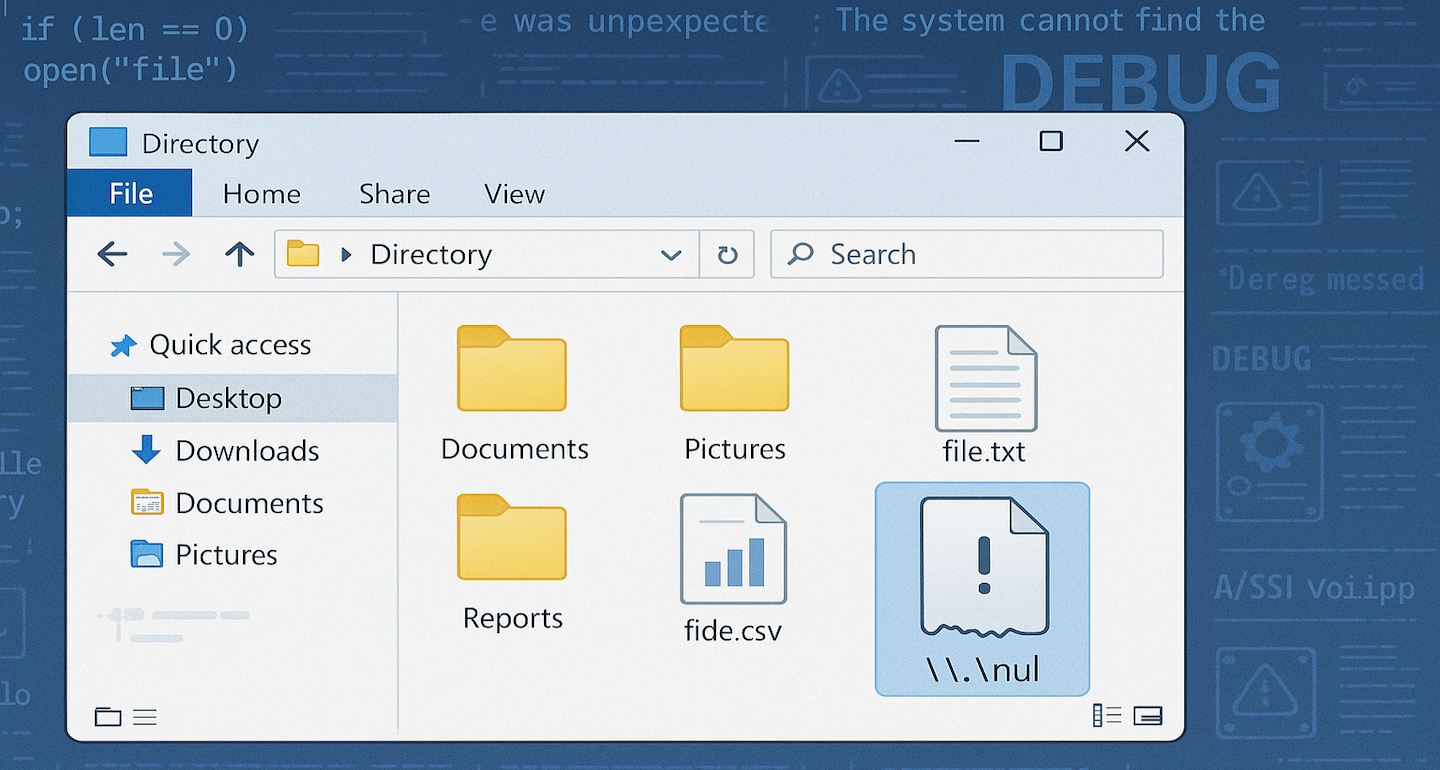

In the last few months my Markdown Monster Application Insights log has been inundated with a hard failure for lookups of a \\.\nul device error. In my logs this shows up as an error like this:

Figure 1 - Null device errors in the Application Insight logs

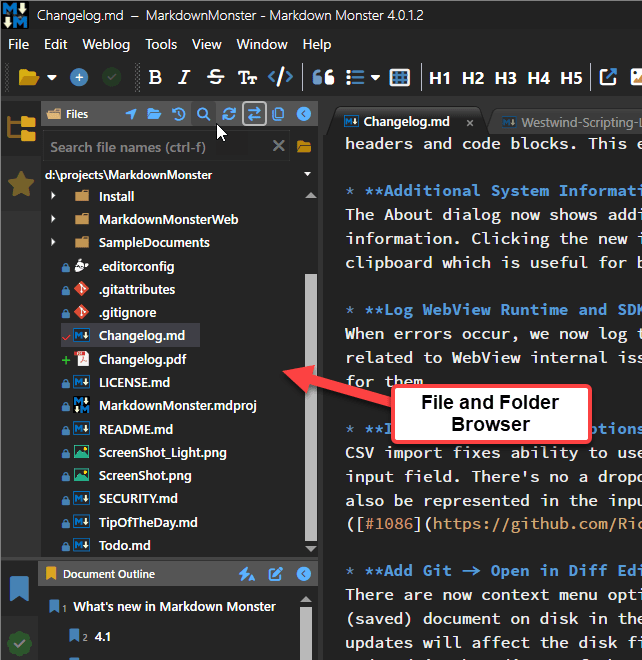

This error started creeping up in my logs a few months ago, and since then has gotten more frequent. The error always occurs in the same location in the code and it's related to the File and Folder Browser in MM that displays the files available on the file system.

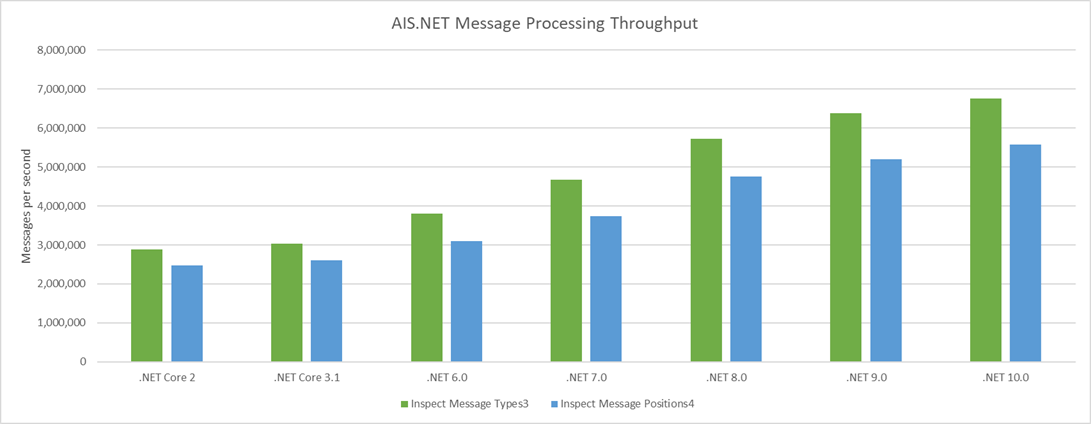

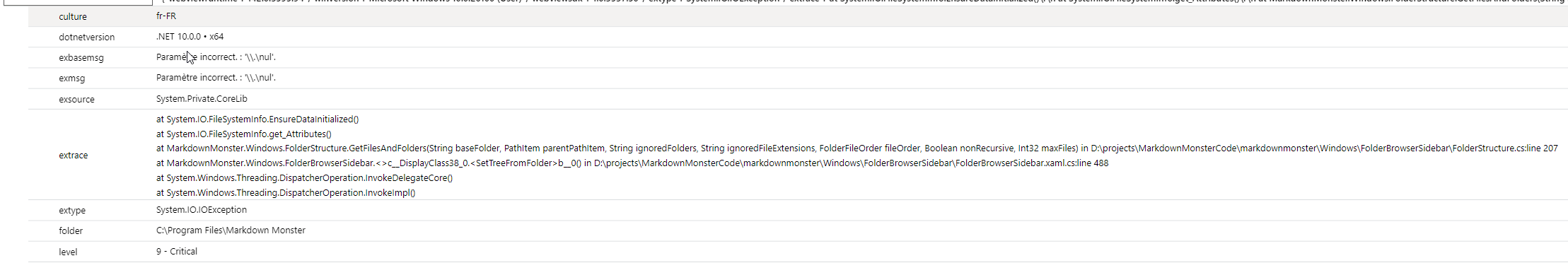

Figure 2 - The File and Folder Browser in Markdown Monster that is the target of the error

This is a generic file browser, so it's very susceptible to all sorts of oddball user configurations and mis-configurations and this particular error likely is of the latter kind. However, after doing a bit of research this is not an uncommon error - there are a number of references to this although the cause of it doesn't appear to be very clear and can be related to various different things.

In my use case, the error itself is triggered by doing a fileInfo.GetAttributes() call on a file name that was returned by the Directory.GetFiles() lookup originally. The file is not a 'regular' file but rather a 'device' and so GetAttributes() throws an exception. And yeah that's very unexpected.

Specifically the failure occurs here:

// System.IO Exception: Incorrect Parameter \\.\nul

if (fileInfo.Attributes.HasFlag(FileAttributes.Hidden))

item.IsCut = true;

This code sits inside of a loop that does a directory lookup then loops through all the files and adds them to the display tree model that eventually displays in the UI shown in Figure 1. The key is that the Attribute look up fails on this mystery 'null device' file.

This is doubly frustrating in that Attributes is an enumeration that apparently is dynamically evaluated so the only way to detect the invalid state is to fail with an exception. Bah 💩!

What the heck is \\.\nul?

My first reaction to this error was, yeah some user is doing something very unusual - ignore it. And yes, the error is rare, but there appear to be a number of different users running into this issue (oddly all are Eurozone users - so might be some specific software or AV).

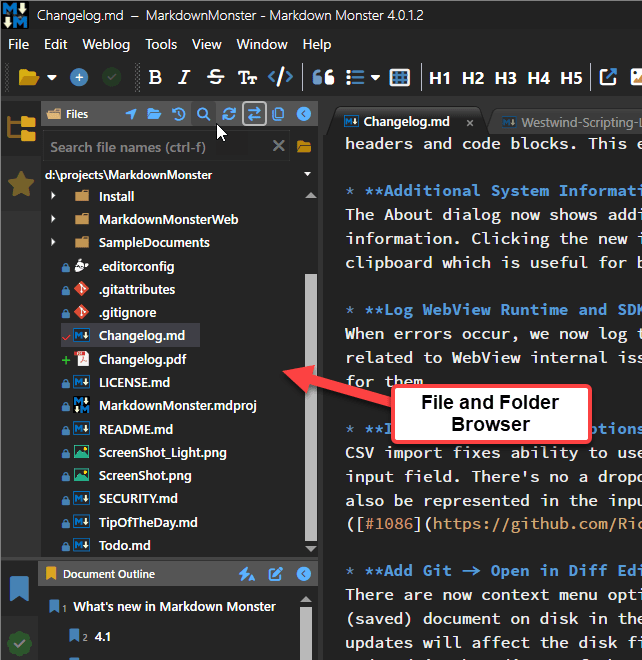

I started looking into it more doing some LLM research.

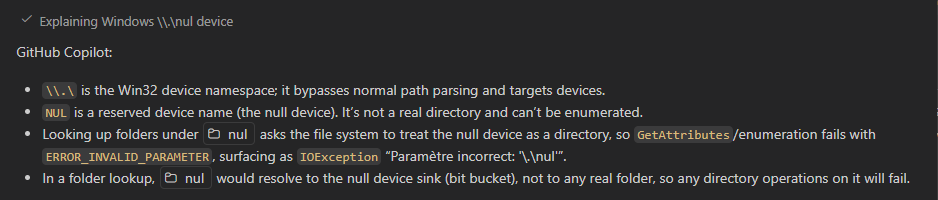

The first response is what I pretty much got as a standard explanation of a null device:

Figure 3 - Basic LLM definition of a null device in file context

Turns out nul refers to a the Windows nul device, which as the name suggests is a device sink that doesn't do anything. Apparently, it's meant to be used to pipe or stream STDIN/OUT to oblivion. I'm not sure how that would ever end up in a directory listing unless it's mapped through some weird symlink redirection. While symlink mis-configuration is not hard to do in Windows, it's odd that several users would end up with the same nul device error misconfiguration.

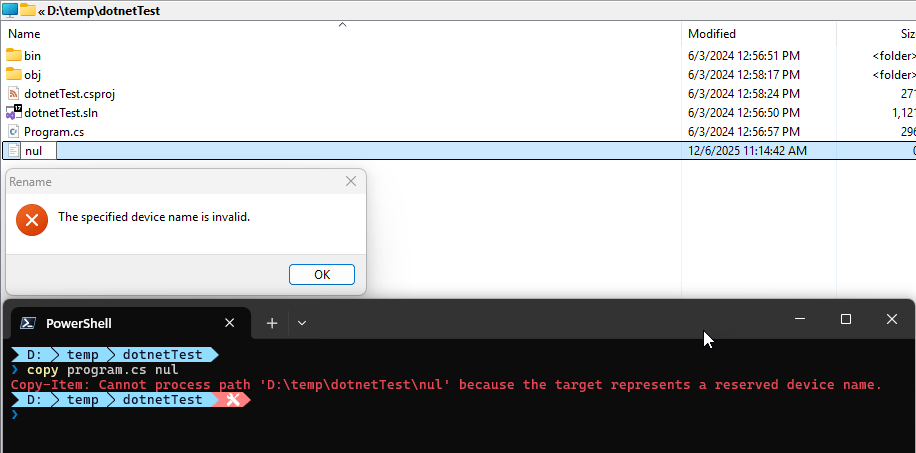

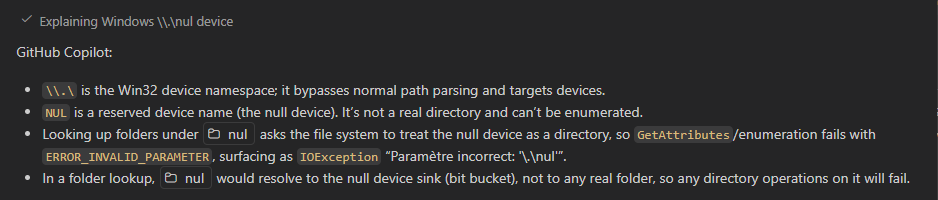

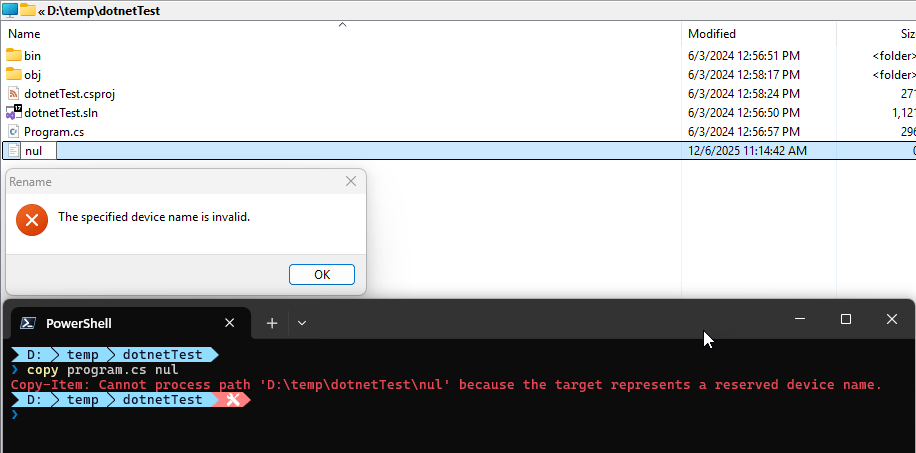

Furthermore it seems that Windows itself forbids creation of files or folders with the name of nul:

Figure 4 - nul files and folders can't be created in Explorer or the Shell

So - it's still a mystery to me how a \\.\nul entry can sneak into a directory file or folder listing.

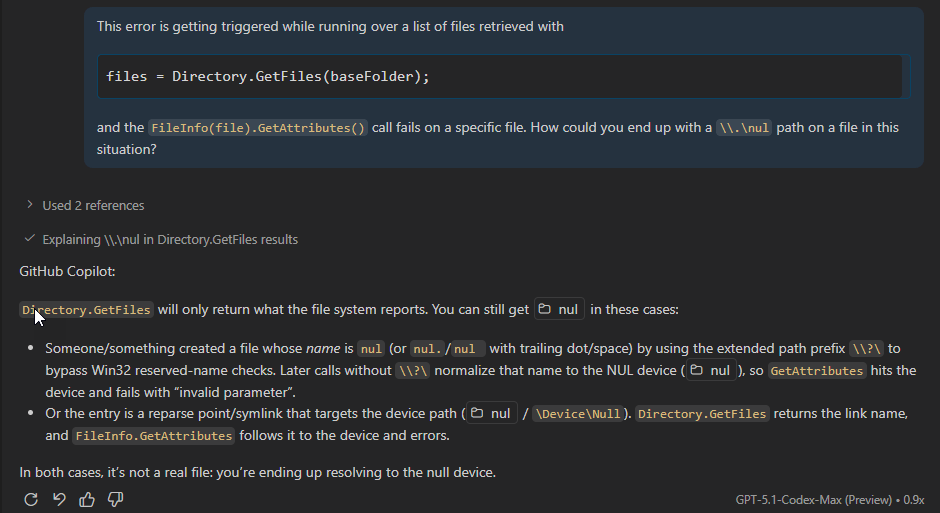

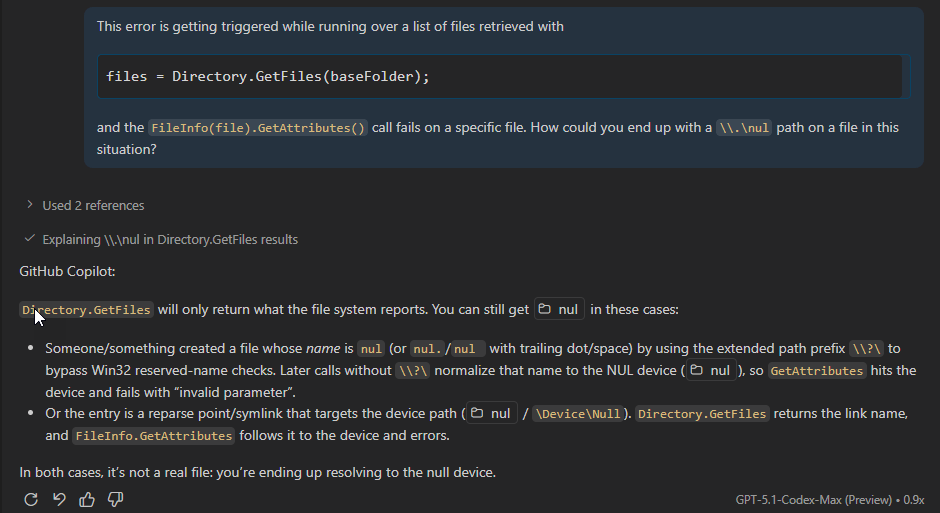

The second prompt tries to unravel the file listing mystery, but the answer (similar for various other LLMs) is not very satisfying:

Figure 5 -

The first point is unlikely since we've already seen that it's rather difficult or impossible to create file or folder with the name of nul.

The latter is more interesting: Some sort of mis-configured symlink reference. However, I couldn't find a scenario where a symlink would do this. Doing directory listings on folders that have symlinked embedded folders (like Dropbox, OneDrive etc.) seems to work fine and returns those linked folders the same as normal folders and you can get attributes on those (although they are often empty).

But I suppose it's possible that a symlink could have an invalid reference to a nul file name. I didn't try this as surely I would mess something up irreversibly (as I always seem to do when manually messing with symlinks on Windows).

Working around

In the end I was unable to troubleshoot the exact cause of the problem, but given what we know there are workarounds at least.

So far since implementing the first of the two solutions I haven't seen the errors pop up any more in newer versions. However, I still see the older version errors which suggest that the users having these issues haven't gotten updated to newer code yet.

So here are the two workarounds I've used for this:

Bobbing for Apples - eh Errors

This falls into the simplest thing possible bucket:

My original solution before I completely understood the problem was to simply check for failure on the code that was failing and defaulting the value. This is a pretty obvious band-aid solution and it works. I haven't seen this error crop up in versions since this simple fix was originally made.

try

{

if (item.FileInfo.Attributes.HasFlag(FileAttributes.Hidden))

item.IsCut = true;

}

catch {

// if we can't get attributes it's some device or map we shouldn't show

item.IsCut = true;

}

The idea here is that if attributes cannot be retrieved the file cannot be a 'normal' file that should be displayed and we can safely omit rendering it.

Although this works it's always a little unsatisfying to fix things in this band-aid manner. Specifically because it might crop up elsewhere again - completely forgotten then. 😄

Filtered Directory Listings

The source of the problem really seems to be that the directory listing is retrieving device data in the first place.

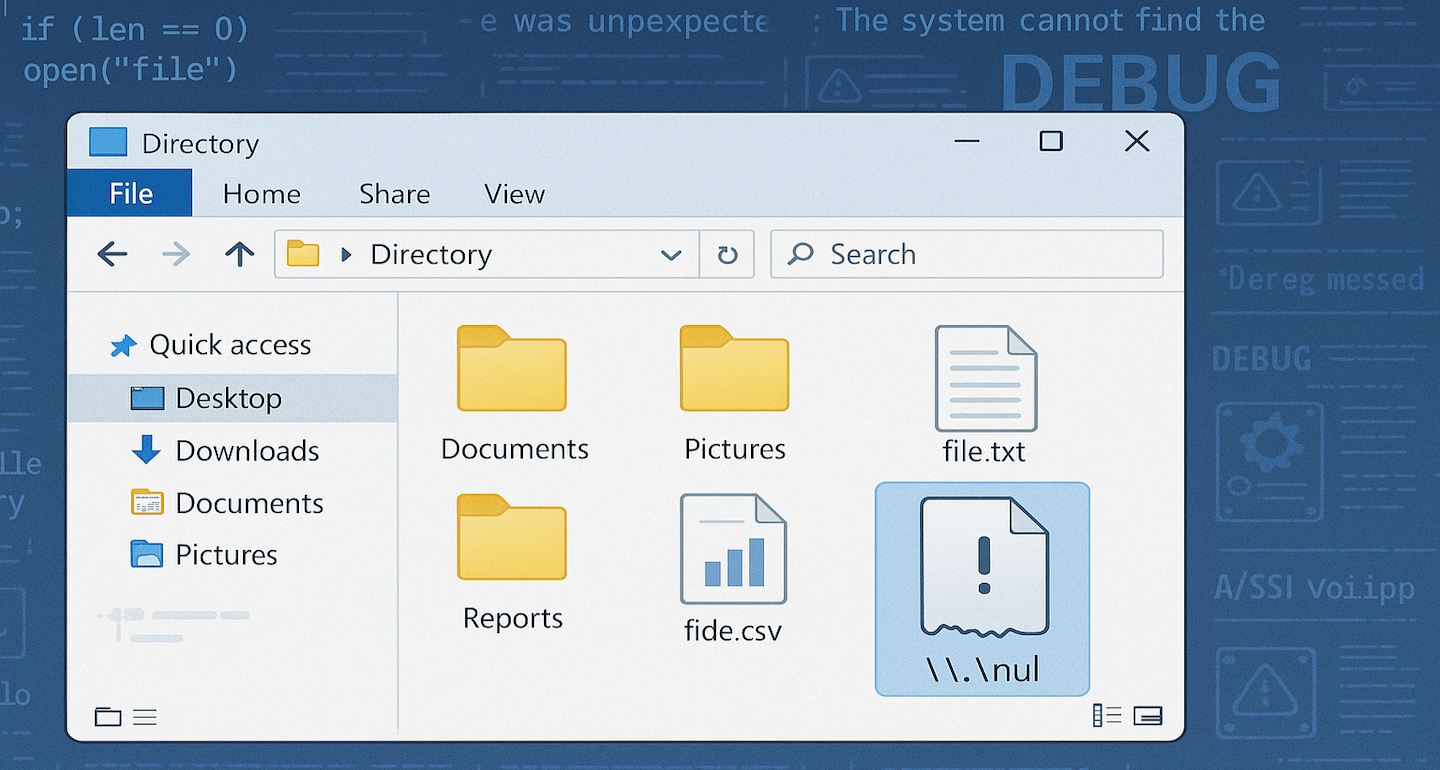

It turns out the default Directory.GetFiles() filter mode is rather liberal in what it retrieves using the default EnumerationOptions instance:

Figure 6 - Default enumeration mode doesn't skip Devices

It only skips over hidden and system files, but allows everything else.

The \\.\nul error is caused by a Device map of some sort so skipping over devices might be useful.

So, rather than using the default directory listing, we can use explicit EnumerationOptions and skip over devices, like this:

string[] files = [];

try

{

var opts = new EnumerationOptions { AttributesToSkip = FileAttributes.Hidden |

FileAttributes.Directory | FileAttributes.Device |

FileAttributes.ReparsePoint | FileAttributes.Temporary};

if (config.ShowAllFiles)

opts.AttributesToSkip = FileAttributes.Directory | FileAttributes.Device |

FileAttributes.ReparsePoint;

files = Directory.Files(baseFolder, "*.*", opts);

}

catch { /* ignore */ }

foreach(var file in files) { ... }

Keep in mind that this is for a widely used generic implementation so there's a extra safety built in here with the try/catch to protect against invalid user provided folder names etc. from throwing out of the app. In that scenario there's no file list returned.

The code above should prevent devices and reparse points - which are likely the cause of the \\.\nul device errors I'm seeing in the log - to stop occurring as they are not being returned by the directory listing.

Summary

Since implementing this fix the logs have been clean of the errors. Since I never had a repro scenario I can only go off my logs though so I can't be 100% certain that the problem is solved, but using both the directory skip filter plus the exception handling around the Attributes retrieval most definitely should fix this issue.

To be clear this is a huge edge case for a very generic file browser solution that's going to get all sorts of weird shit thrown at it from many different types of users from power users to your grandma's file systems. In more controlled situations you probably don't have to worry about edge cases like this.

However, it's important to remember that there can be funky behaviors with filesystem behavior related to symlinks and remapped folders (like DropBox). For example, I just ran into an issue where FileInfo.Exists reports the Dropbox folder as non-existing where Directory.GetDirectory() does. IOW, symlinked files and folders can have odd behaviors and in those scenarios where you're dealing with symlinked file artifacts it might be a good idea to explicitly specify the file attributes to avoid unexpected failures that can't be easily handled with predictable logic.

© Rick Strahl, West Wind Technologies, 2005-2025