I recently spoke to my friend’s daughter, who has had a lifelong ambition to be an illustrator. Despite being extremely talented, she has decided to go in a different direction at university, telling me, “AI means that no one will pay artists to make art.”

I’m not convinced she is right. But if this pattern plays out repeatedly, the creative industries will be starved of fresh talent.

Copyright, which exists to protect and regulate a piece of work — whether it’s a book, painting, piece of music or software — might protect creative professionals in the short term. However, the status of copyright with regard to generative AI is not settled.

And trampling on copyright is only one of several ways in which generative AI can create new categories of harm that we’re not prepared for. Vulnerabilities loom in compliance and data privacy, governance and security. GenAI systems also pose risks to our already fragile environment and our psychosocial well-being.

Who will protect us from the downside of GenAI? The truth is, as we rapidly ascend the learning curve of this new technology, we must also be the ones who ensure that it’s used safely, even as we wait for organizations and governments to catch up with it.

Copyright Threats for Coders and Other Creators

Let’s look first at copyright. With the advent of photography, new debates arose around copyright, and parallels can be drawn with the current debates around AI and copyright. Was the reproduction of photographic work an act of infringement, and should the photographer be able to control it? (Yes.) Should photographs themselves be protected as copyrightable works? (Again, yes.)

For generative AI, it is no secret that training a large language model (LLM) requires a large corpus of material. There is no informed consent regarding how that material is obtained. AI companies know what they’ve ingested but are not compelled to share the sources of their data.

So, as an author, artist, photographer, composer — or developer — it is very hard to ascertain whether your work has been used in LLM training, although if the work is published on the internet or appears in LibGen, it almost certainly will have been.

Like a burglar arguing that they can’t turn a profit if they can’t break into your house and steal the contents, AI companies have chosen to ignore copyright, arguing that licensing the material would be too expensive or difficult, and their businesses aren’t viable if they have to pay.

The results of ignoring centuries of legal precedent are predictable. On Friday, the AI company Anthropic, facing largest copyright class action ever certified, agreed to pay $1.5 billion to a group of authors and publishers after a judge had ruled that the company had illegally downloaded and stored copyrighted books.

In addition, Disney and Universal have each filed a lawsuit against AI image generator, Midjourney, accusing it of piracy. And the BBC is also considering legal action over the unauthorized use of its content.

What’s remarkable about the Anthropic case is that judge, Judge William Alsup, of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, has largely sided with Anthropic.

In June, he issued a summary judgment saying that, when the company acquired books legally, its use of them for AI model training was legal. But when it downloaded volumes from “shadow libraries,” Alsup ruled, Anthropic’s leaders knew it was using pirated books.

Alsup is the same judge who previously held that APIs cannot be copyrighted, thereby torpedoing Oracle’s landmark 2012 case against Google’s Android.

In the U.K., where copyright originated, government attempts to weaken copyright to favor AI companies are so far being thwarted by the House of Lords. But the government’s intention is clear; it has chosen to bet on future economic growth from AI against existing revenue and potential growth from the U.K.’s already successful creative industries.

In the U.S., an early version of the federal “Big Beautiful Bill” prohibited states from regulating AI technology for 10 years, so as not to hamper AI industry growth. (The final version of the bill, signed by President Trump, did not include that provision.)

It seems likely that if the use of AI in creative endeavors becomes normalized, the copyright question may well become moot — particularly if the industries are starved of skilled creators.

The Ethical Dangers of AI Data Screening

Copyright is also a compliance issue. If you don’t know the provenance of your training data, you’re not only undermining creators but also exposing your company to massive supply chain risk.

Once acquired, these data sets have to be screened. This is carried out using a technique called reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF). Taking a leaf out of the social media playbook, AI companies expose workers in countries such as Kenya to an endless stream of horrific content for the princely wage of $2/hour.

The results of RLHF, as Time and The Guardian have reported, are shocking. Unfortunately, beyond these excellent pieces of journalism, not much attention is being paid to this issue.

“I’ve now sat on two panels where I was told that RLHF workers are just collateral damage,” Marisa Zalabak, AI ethicist, psychologist and co-chair of the AI Ethics Education committee for IEEE, told The New Stack.

If we keep treating these harmed humans as “collateral,” we’re baking exploitation into the AI supply chain itself.

As well as being reticent to share what they train on, the big AI companies have also been guarded about their environmental impact, although we know that both training LLMs and using them for inference creates considerable environmental damage. I recently explored strategies to significantly reduce some of these environmental harms in The New Stack.

Since writing that article, Google has become the first big tech company to produce a report on the impact per text query of its LLM, and that’s extremely welcome. Google reports large efficiency gains over the last year, noting that its per-query energy use was 33 times higher 12 months ago. Unfortunately, they are focused only on the marginal energy used per AI prompt, and are not looking at the energy used for training, end-user devices or external networking.

One aspect of this that seems to cause particular confusion is a side effect of the extremely rapid growth of GenAI, which concentrates detrimental effects in particular areas. While individual communities are experiencing the very real negative environmental effects of AI data centers (most notably, the environmental nightmare around xAI’s Colossus), the impact of running an individual query through an LLM is comparatively small.

Why GenAI Poses New Challenges for Governance

As we move from training to operating LLMs, there are certain qualities of generative AI that pose ethical challenges that our existing AI governance systems don’t handle well.

AI ethical harms are commonly subdivided into allocative and representational:

- An allocative harm is when an AI system rejects you for something you were entitled to, such as a loan.

- A representational harm is one where a change occurs psychologically to individuals or communities on the basis of how they see themselves represented.

We have good mechanisms for allocative harms. Representational harms, though, are more ambiguous and harder to measure.

“As researchers, we’re aware of representational harms, but they are perhaps harder to quantify,” Gaia Marcus, director of the Ada Lovelace Institute, told The New Stack.

“Our research on Gen AI use in U.K. schools suggests it is mainly informal use of generic AI products such as ChatGPT, rather than more specific AI EdTech,” Marcus said. “This could really open up the question of representational harms, if sufficient safeguards aren’t in place.”

Allocative and representational harms do overlap. A recent study by the London School of Economics and Political Science found when asking Google’s AI information tool, Gemma, about health issues, it had a distinct gender bias and underplayed female symptoms.

“If you are a case worker making decisions based on a tool that gives biased outputs the outcome would be an allocative harm,” Marcus said. “Whereas if you were using a system to play back your own thoughts, that might be representational, but it’s likely harder to track and quantify it over time.”

She added, “If a chatbot becomes the sole interface between the individual and the internet, and therefore the main way they get news and engage with the world, the risks from representational harms could become quite large.”

The Security Risks of Code Generation

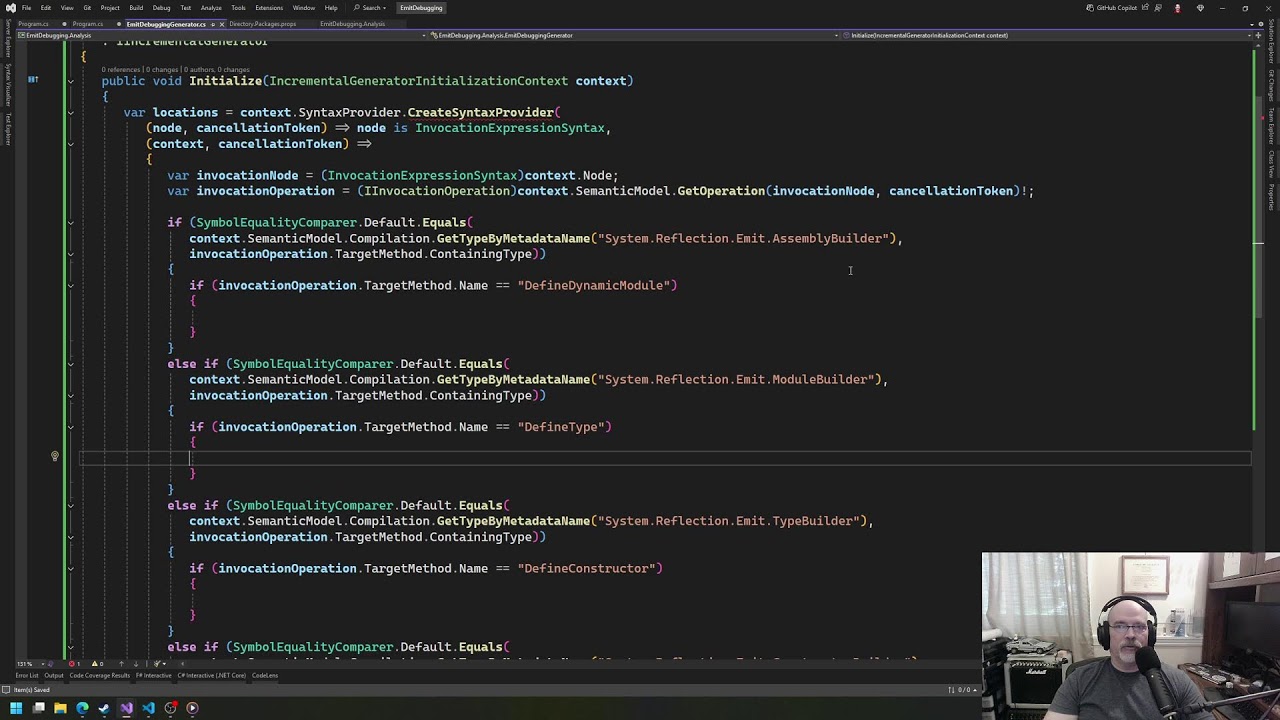

One place where GenAI appears to have early product-market fit is programming. It feels like a natural extension of the cloud native approaches, which have allowed organizations to run more experiments.

“GenAI is great for proof of concept work,” Sal Kimmich, technical director and principal security compliance consultant at GadflyAI, told The New Stack. “You’re getting a lot more prototypes and engineering energy out of the same people in the same amount of time, without replacing what the humans are actually for—which is innovation, with minimal harm.”

Kimmich believes that 20% of engineering effort should be spent building out POCs and experimenting with artificial intelligence. Before your organization does this, however, they recommend that every single person in your company undergoes some ethics and data security training.

“Make the expectations of compliance very clear, even if your employees are working without corporate surveillance at the time of building an MVP,” or minimum viable product, they said. “At the end of the day, the lawsuit will sue a human being and you have to ensure that you had every compliance in place to do least harm.”

Generative AI systems are stochastic rather than deterministic; given apparently identical inputs, they will produce different answers. This stochastic nature means that you should never let an AI near production code, Kimmich told The New Stack, because you cannot trust it. “It is clunky, it might have vulnerability concerns, and it doesn’t engage the developers in long-term architectural decision-making.”

Agentic systems — agent-to-agent architectures that communicate with each other through LLMs — exacerbate the problem of stochastic systems since they produce cascades within LLM chains. “Understanding those cascades is really hard, and the more of these models you put together, the more variability comes into the system,” said Kimmich.

The measurement demands of GenAI-based systems are therefore high. Kimmich suggested an alternative to bulk testing — applicable where you have humans in the AI loop. It is based around sojourn time, which describes the time a system spends in a transient state before transitioning.

“We want to model the best relationship between human and machine, by measuring that human’s behavior over time,” Kimmich told us. “By creating a semi-Markov Chain that has some prediction of how that individual is likely to respond, you have something that can act as an anti-breakout mechanism.”

The more highly regulated industries, such as finance and health care, are already handling AI with the highest level of security, all the way down to the physical hardware. There is an issue though, according to Marcus.

LLM-based tools are often used to condense text and we’re seeing these summarization tools used in health, or “chatbot wrappers around an LLM in therapy — either as part of a formal tool or ‘off-label,’” she said. “But the precautionary principles of not rolling out a health product until it has been substantially tested don’t currently apply for general-purpose tools that aren’t marketed as a health product.”

Kimmich thinks regulatory structures will follow a critical mass for security posture. “I think there’s going to be a second set of new, regulated industries because of artificial intelligence and the nature of massive data storage and usage, especially personalized data,” they said. “This is because of the problem of unicity—the ability to capture these databases.

“If I have somebody’s Netflix account information and any other intersecting information about them, I can identify them. So creating regulated spaces to reduce the risk of individuals from data breaches is inevitable.”

From a security standpoint, a lot of the threats from GenAI are based around data dumps. “An easy way to avoid these threats, and the associated carbon burning, is to rate limit the generative outputs to the speed that a typical human can read them,” said Kimmich. “This means it churns really slowly and the likelihood of having a dangerous data dump before it’s realized is drastically reduced.”

The Potential for Psychosocial Harms

For IEEE’s Zalabak, who has a particular interest in psychosocial well-being, the anthropomorphization of AI is her top concern. Meta has been in the news recently for allowing chatbots to have sensual conversations with children. “The sexual language that Meta allowed is extremely harmful,” she pointed out. Racist language was also reportedly allowed.

“These programs are designed to emulate emotion, and it’s a deceit,” Zalabak told us. “There is no reason for them to pretend to be a person, using human pronouns to refer to a machine.

“This can lead to psychotic episodes, such as the boy in Florida who died by suicide, and the autistic teen in Texas who was told to kill his parents in response to them limiting his screen time. Both were using Character AI, and they are not one-offs. Psychologically, we are sending people into a dual consciousness state where they have two identities, one of which is in a fake world.”

Marcus suggested that, as with any new technology, it is important we resist the temptation to divide people into doomers versus boosters.

“We’re seeing a number of disjoints that are common for any big technological change that isn’t being stewarded,” she said. “The disjoint between the pace of technology and the ability to regulate it: The disjoint between politicians who want less red tape, and the general population who want more governance.

“It is really hard to align the pace of change with existing mechanisms to find unanticipated harms on populations.”

Marcus sees real potential for nested harms. “Using AI responsibly is a challenge because there are so many nested issues,” she told TNS. “You’ve got tools that are marketed directly to consumers, being used off-label in professional contexts without guardrails. The pace of technical rollout essentially means we are experimenting on millions of people at once, without evaluating or understanding the effects in the round.

“You may have this idea that 2025 will be the year of the agents but we don’t have the liability sorted out. So it becomes really hard to understand the part of the puzzle you are trying to lock down and its ethical consequences.”

On the whole, Marcus suggested, the AI vendors are devoting a lot of research to existential risks but focusing less on more immediate threats. “A lot of the measurement science in generative AI is focused on catastrophic potential, such as bio and chem risk or loss of control, rather than the harms we are seeing now.”

‘Never Forget We’re Talking to a Machine’

None of the experts I spoke to are anti-AI. “I love technology,” Zalabak told us. “I watched the moon landing and grew up watching ‘The Jetsons’. To me, AI ethics is about embracing the good potential for AI, which is phenomenal. We can do good things with these tools and be profitable.

“But in the meantime, there is so much damage being done. We don’t need robots that look like humans, or humanized language in AI systems. A great deal of harm could be prevented by programming AIs to make it much harder for us to suspend disbelief so that we never forget we’re talking to a machine.”

As I was finalizing this article, news broke that a California couple are suing OpenAI over the death of their teenage son, alleging that ChatGPT encouraged him to take his own life. In an Aug. 25 post on its website, OpenAI said that, “recent heartbreaking cases of people using ChatGPT in the midst of acute crises weigh heavily on us.” The company acknowledges that “there have been moments when our systems did not behave as intended in sensitive situations.”

As the domain experts, it is incumbent on us to try to make sure the technology we create is used appropriately. Nobody else is better positioned to do so.

The post Why Tech Professionals Must Lead the Charge on GenAI Safety appeared first on The New Stack.