We're launching a new blog post series where we share glimpses into our work on Electron. If you find this work interesting, please consider contributing!

Recently, I worked on improving Electron and Chromium's window resize behavior.

The bug

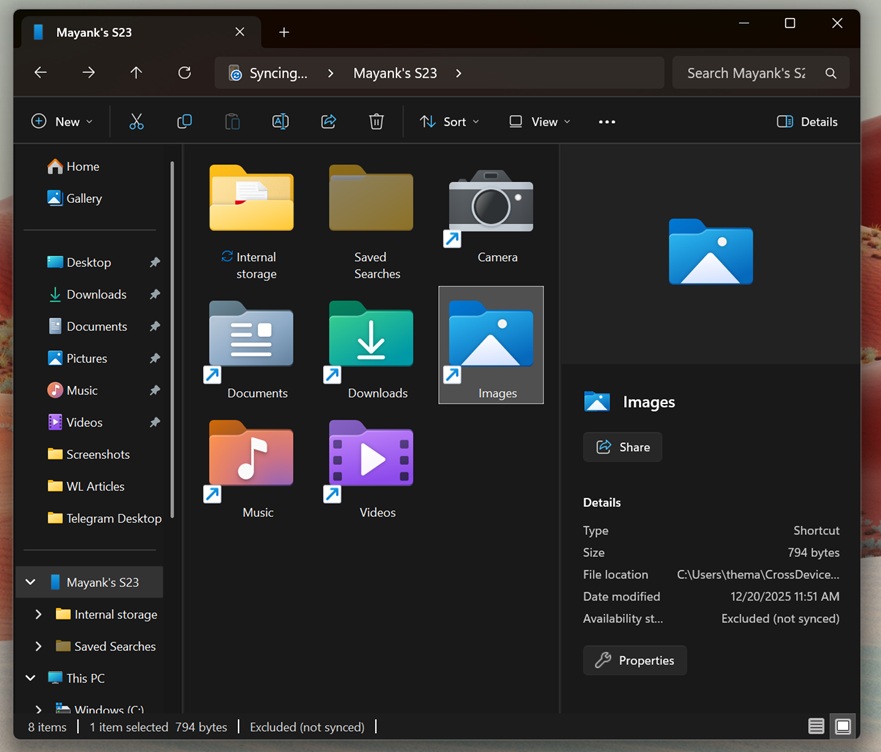

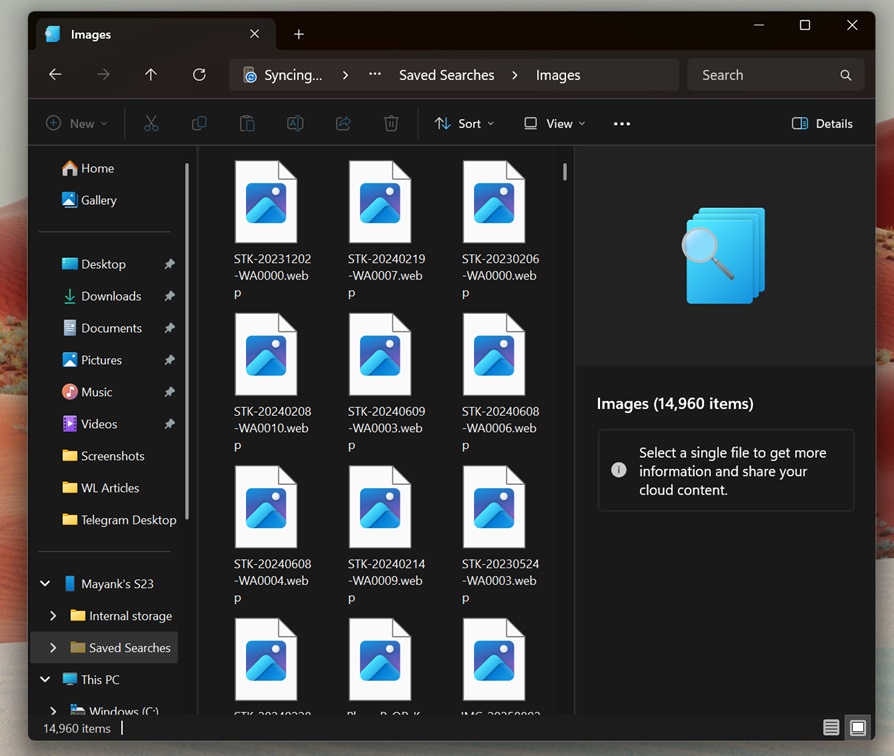

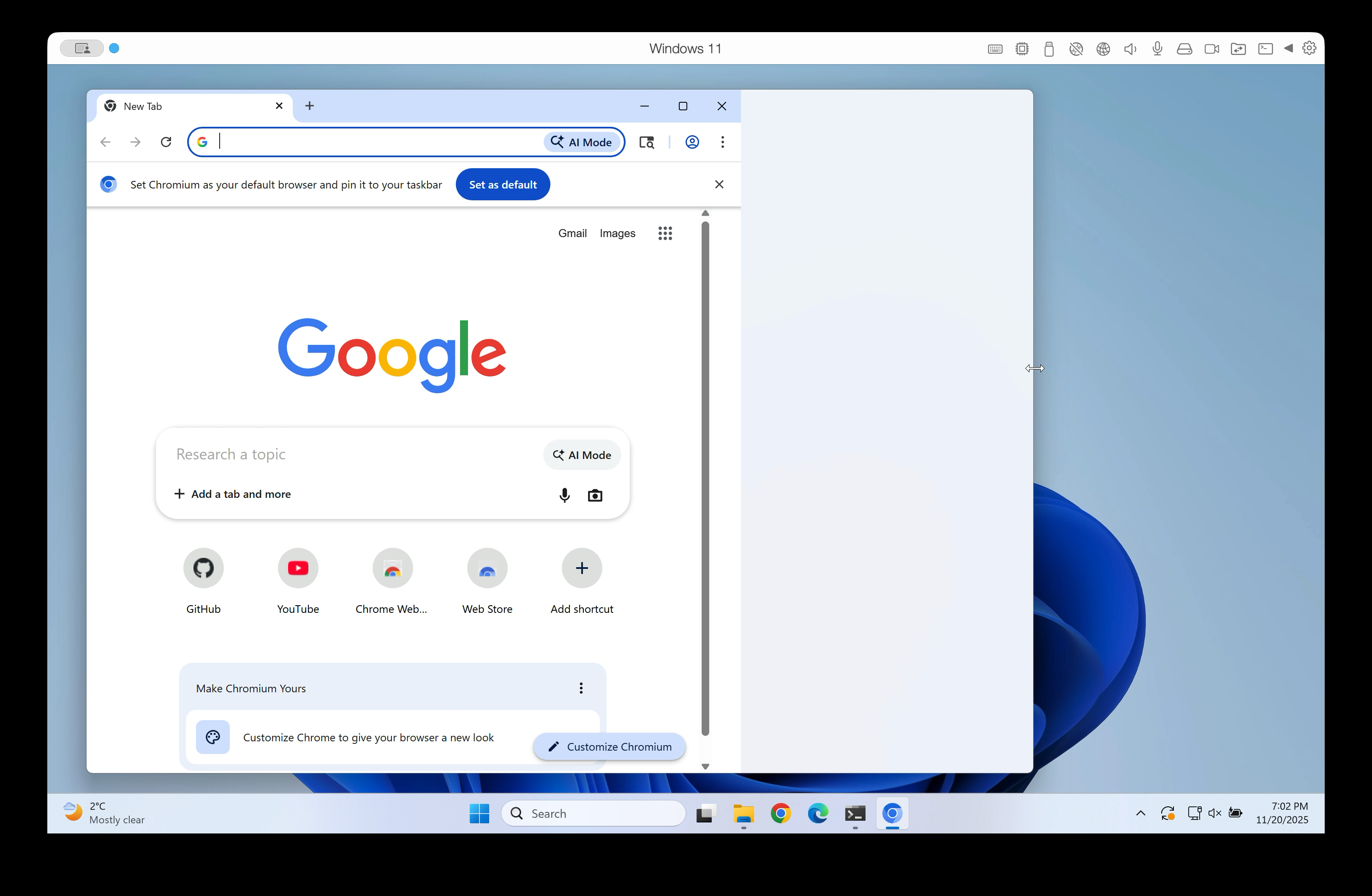

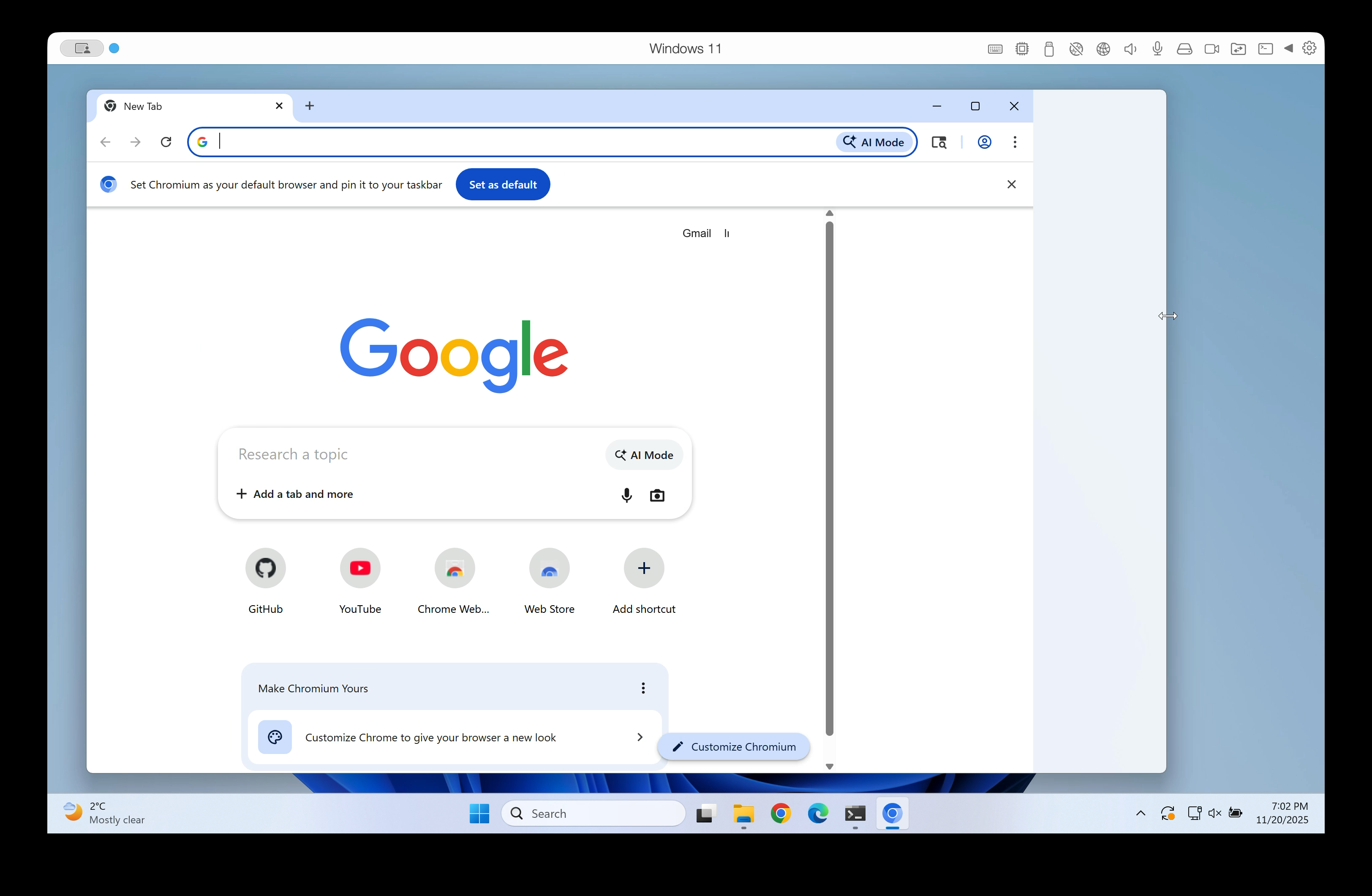

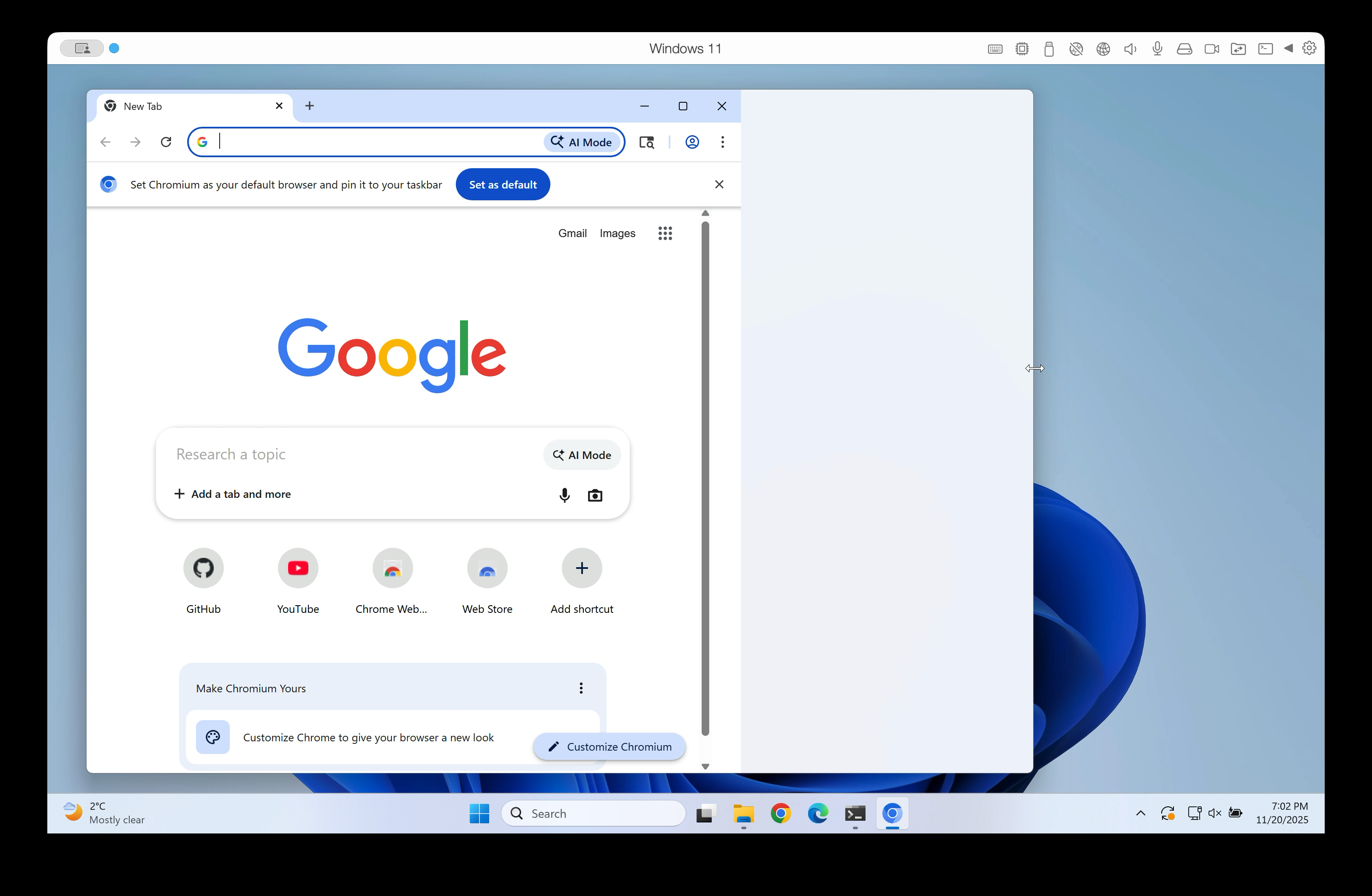

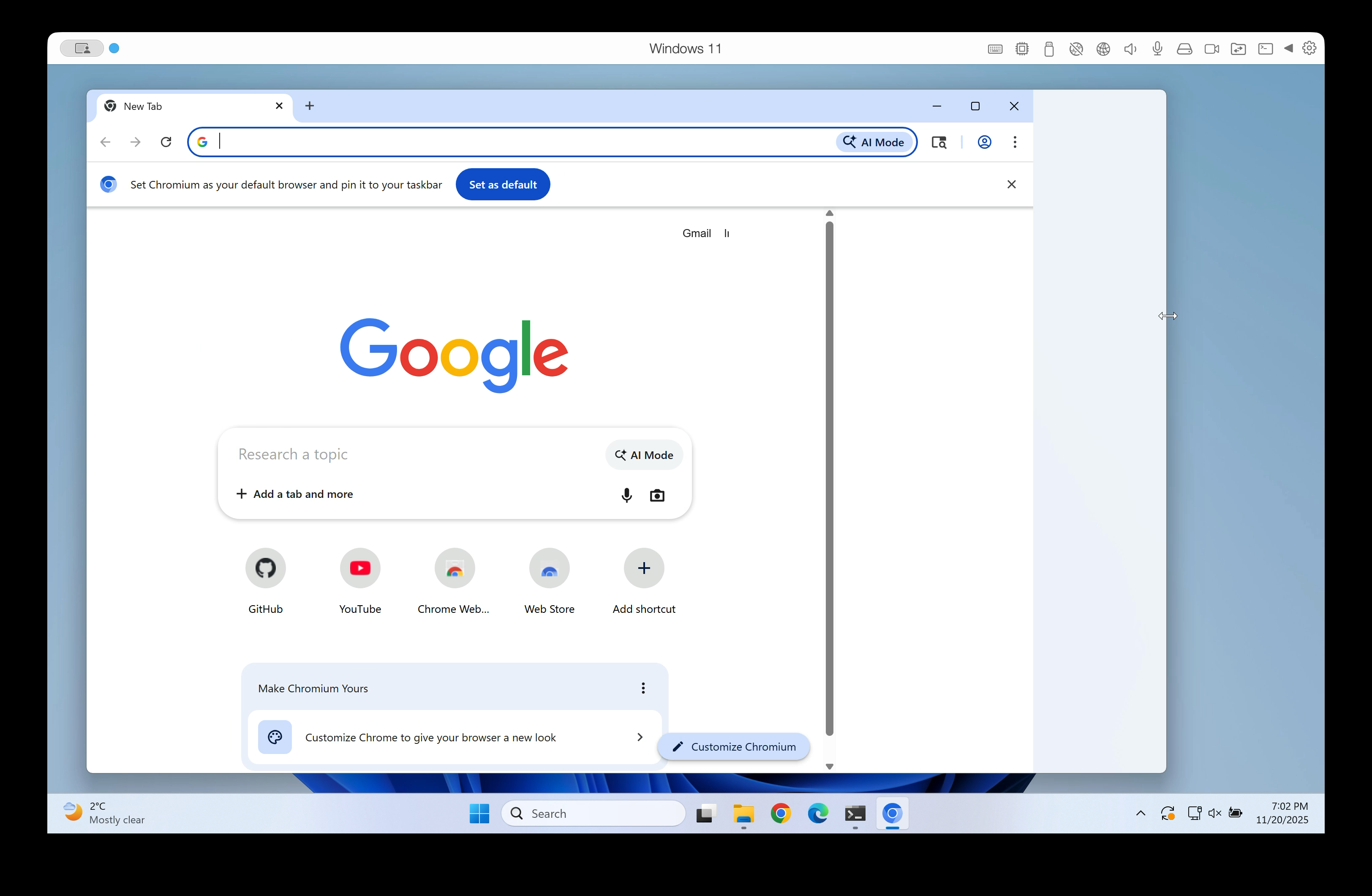

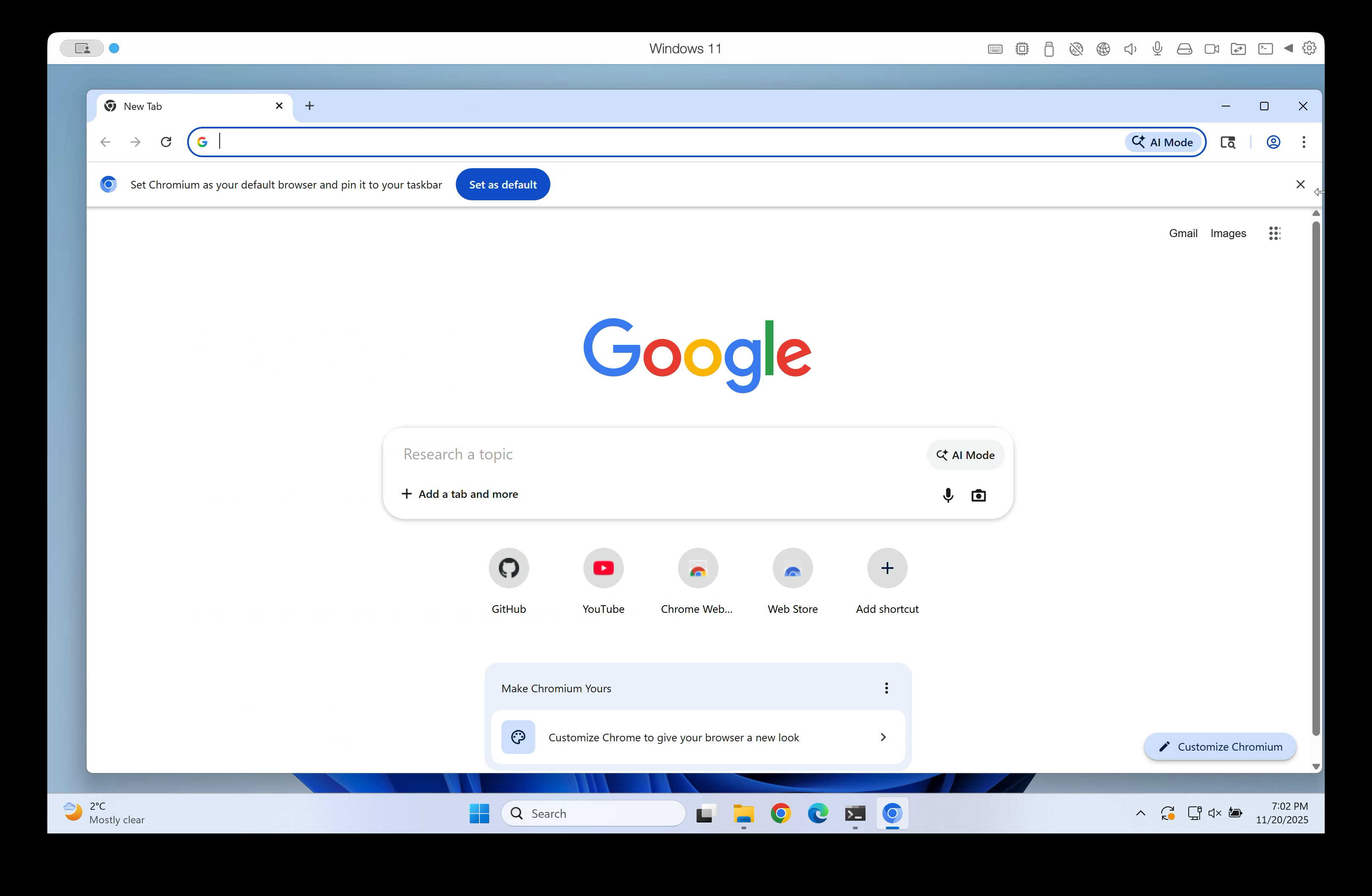

We were seeing an issue on Windows where old frames would become visible while resizing a window:

What made this bug particularly interesting?

- It was challenging.

- It was deep in a large codebase.

- As you'll see later, there were two different bugs under the hood.

Fixing the bug

With a bug like this, the first challenge is figuring out where to start looking.

Electron builds upon Chromium, the open source version of Google Chrome. When compiling Electron, Electron's source code is added into the Chromium source tree as a subdirectory. Electron then relies on Chromium's code to provide most of the functionality of a modern browser.

Chromium has about 36 million lines of code. Electron is a large project, too. That is a lot of code that could be causing this issue.

Narrowing down the root cause

I did a lot of experimentation.

First, I noticed that the issue occurred in Google Chrome, too:

This suggested that the issue was likely in Chromium, not in Electron.

Additionally, the issue was not visible on macOS. That suggested that it was in Windows-specific source code.

The crucial lead

I tried a lot of different command line flags and configuration options.

I noticed that app.disableHardwareAcceleration() fixed the issue. Without hardware acceleration, the issue was gone.

Here is some context: Chromium supports various different graphics APIs for showing pixels on screen (OpenGL, Vulkan, Metal, and more). On Windows, it uses different graphics APIs than on macOS or Linux. Even on Windows, Chromium can work with multiple different graphics backends.

Which graphics backend Chromium uses depends on the user's hardware. For example, some graphics backends require the computer to have a GPU.

I tried various graphics backends and noticed that the following flags fixed the issue:

--use-angle=warp--use-angle=vulkan--use-gl=desktop--use-gl=egl--use-gl=osmesa--use-gl=swiftshader

The following flags reproduced the issue:

--use-angle=d3d11 (this is currently the default on Windows)--use-angle=gl (falls back to Direct3D 11 on Windows, see chrome://gpu/)

None of the working flags were good enough to be used as the default in Electron apps on Windows. They were either too slow or lacked broad driver support.

However, these workarounds pointed me into the right direction. They showed that the issue was in a code path that was only used with the ANGLE Direct3D 11 backend.

Direct3D is a Windows API for hardware-accelerated graphics.

ANGLE is a library that translates OpenGL calls into calls to the native graphics API of the given operating system, here Direct3D. ANGLE allows Chromium developers to write OpenGL calls on all platforms. ANGLE then translates them into Direct3D, Vulkan, or Metal API calls, depending on which graphics API is used.

Locating the relevant Chromium component

Chromium references Direct3D in tens of thousands of places. It wasn't realistic to go through all of them.

By chance, I stumbled across a few helpful debugging flags in the Chromium source code:

--ui-show-paint-rects--ui-show-property-changed-rects--ui-show-surface-damage-rects--ui-show-composited-layer-borders--tint-composited-content--tint-composited-content-modulate- (And more)

They highlight areas of the browser window that were redrawn or updated by different parts of the Chromium graphics stack.

That allowed me to see which part of the graphics stack was producing which output.

In particular, the combination of --tint-composited-content and --tint-composited-content-modulate was really helpful. The former adds a tint to the output of the compositor. The latter changes the tint color on every frame.

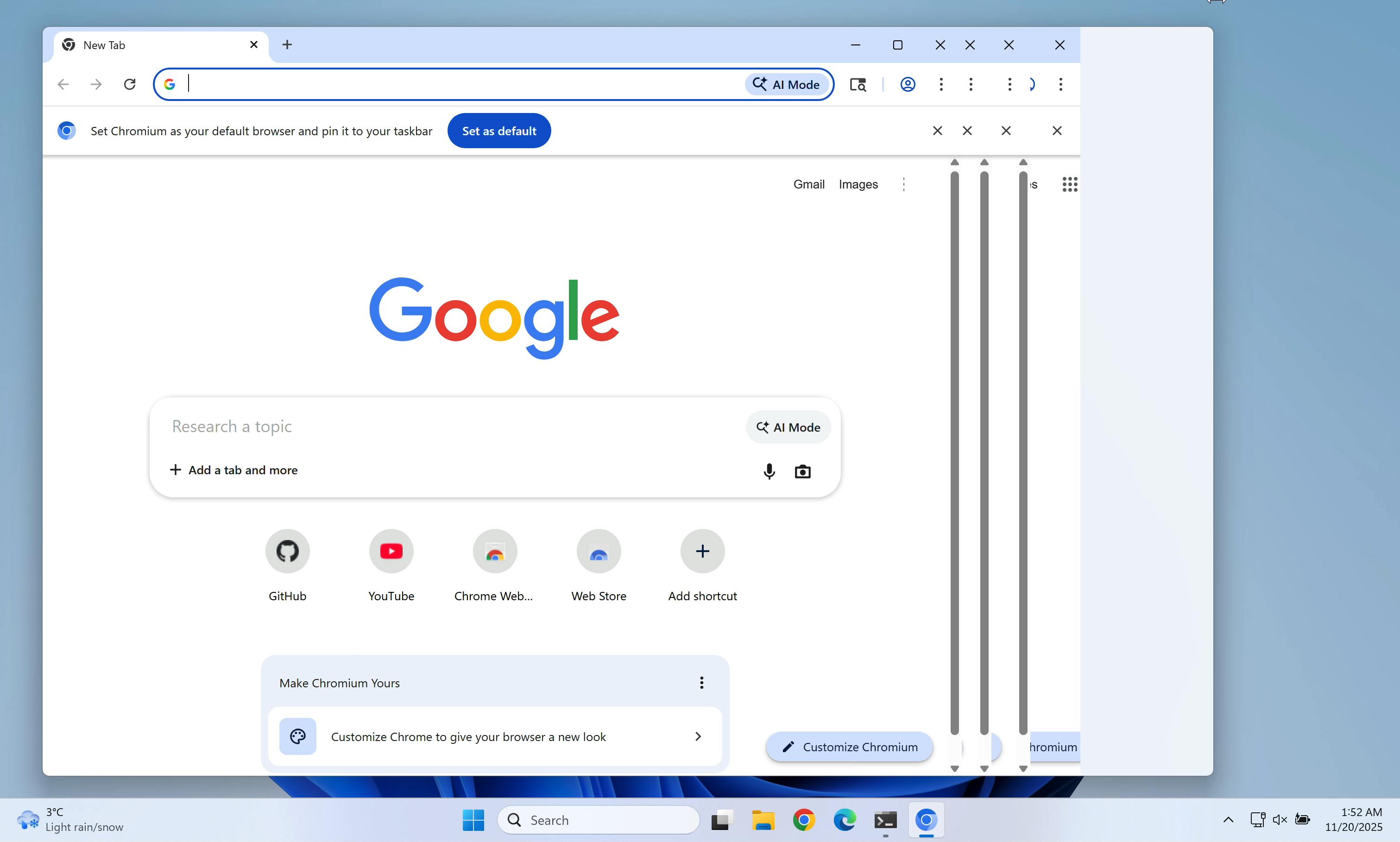

In the screenshot, the cyan-tinted frame was the last frame that was being drawn.

The jank to the right of that frame was not tinted cyan. It was tinted in different colors that were still there from previous frames. This indicated that the jank was not coming from the compositor. The compositor was sending the right output.

The compositor is part of Chromium's graphics stack. The following is very simplified, but for the purpose of this blog post you can imagine it like this:

- The compositor

cc produces a CompositorFrame, which contains draw instructions.

cc sends that CompositorFrame to the display compositor viz.viz then draws the frame and shows it on screen.

Tinting each CompositorFrame showed that the compositor produced the right output. So the issue had to be in the display compositor viz.

Locating the relevant viz code

From there, I started searching for mentions of Direct3D in the viz source code.

Note: From here on, the post will get a bit more technical and reference source code symbols.

I found that on the ANGLE Direct3D 11 backend, Chromium uses the Windows DirectComposition API for drawing the window contents.

Chromium's DirectComposition OutputSurface differs from most other output surfaces in Chromium. It has the capability supports_viewporter (source link 1, source link 2).

An output surface is a bitmap that can be drawn to, often backed by a GPU texture.

Without supports_viewporter, whenever the window size changes, Chromium will create a new output surface matching the new window size. Then it will draw on that surface and show it.

supports_viewporter tries to reduce these costly surface allocations. With supports_viewporter, Chromium will not allocate a new surface on every resize. Instead, it will allocate a surface that is too large for what we need to draw. Then it will only paint to and show a certain sub-rectangle (the "viewport") of that surface on screen. The other parts of the surface are not supposed to be shown on screen.

This is supposed to make resizing more efficient because all Chromium needs to do is pad the surface to the proper width and height instead of allocating a new surface on every resize. This surface resize logic lives in direct_renderer.cc.

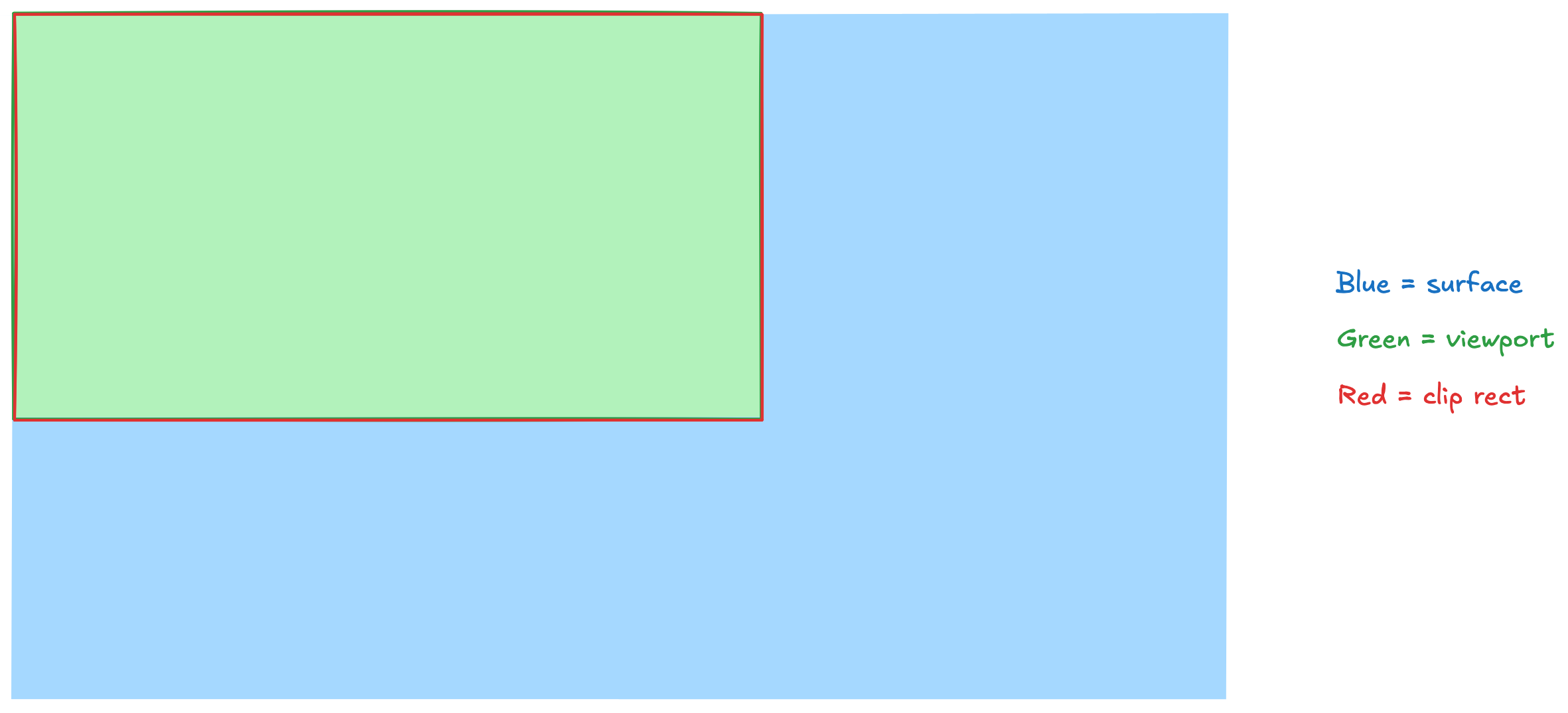

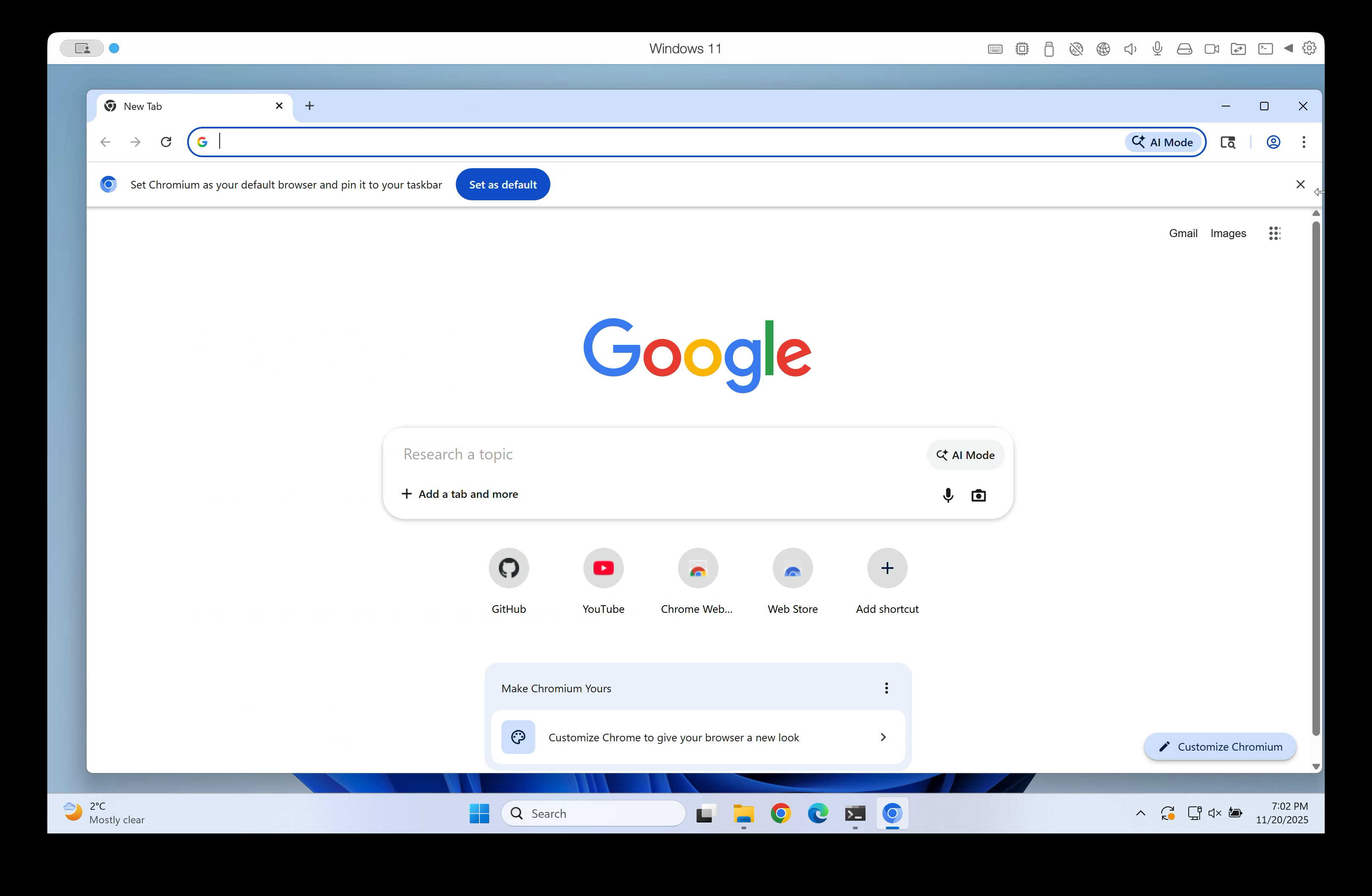

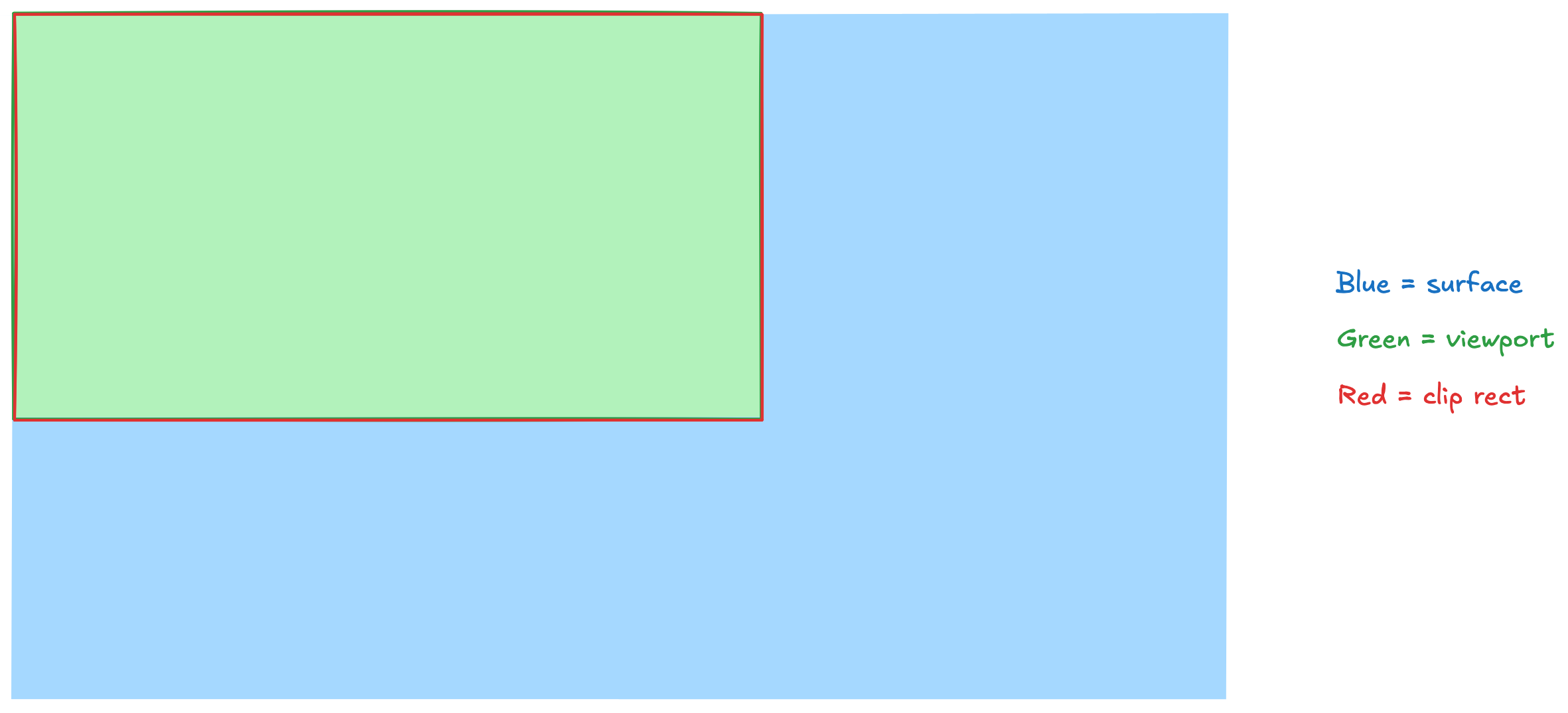

Here's what that looks like:

Let me explain:

- The blue rectangle is our surface.

- The green area is our viewport, i.e., the area of the surface that is supposed to be visible and that we actively draw to.

- The red rectangle is our clip rect(angle), i.e., the part of the surface that is actually being shown on screen.

As a performance optimization, only the viewport (the green area) is repainted when we get a new frame. The rest is left unchanged. This is important. We only ever repaint the green viewport. We don't update the areas outside of the viewport.

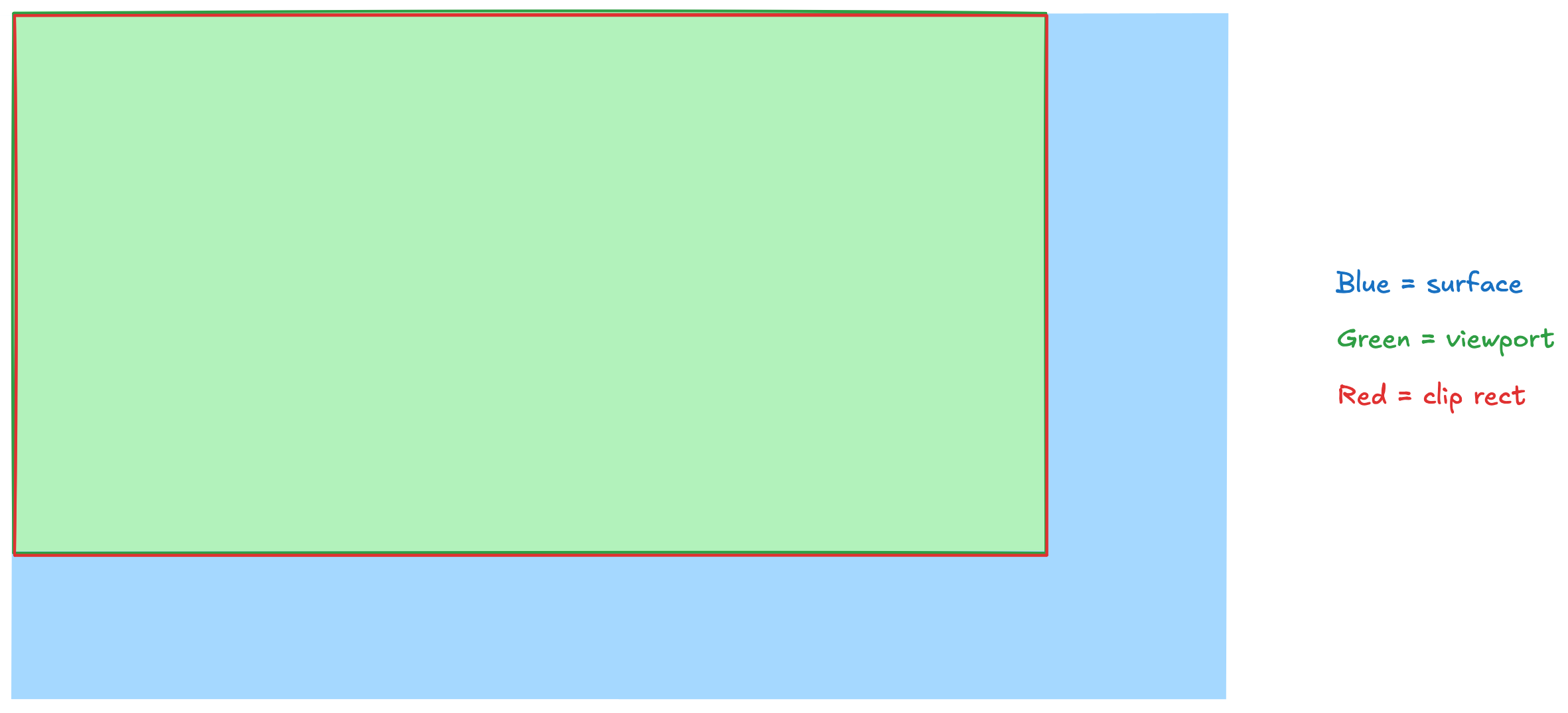

When we resize the window, what's supposed to happen is that in an atomic transaction (= at the exact same time) we repaint the viewport (= the area that's supposed to be visible on screen) and then update the clip rect to clip the surface to the new viewport size.

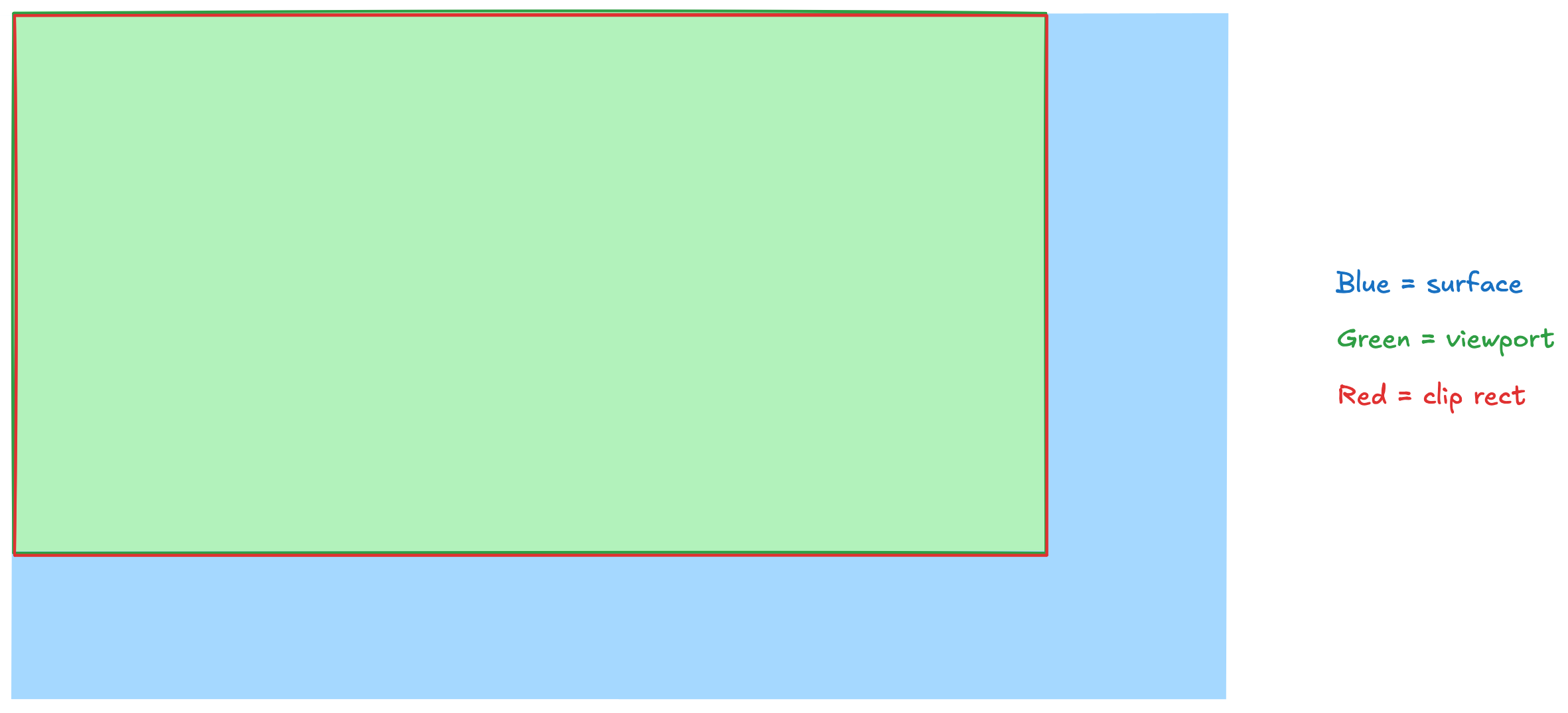

After the resize, it should look like this:

And that's where we get to the first of our two bugs.

First bug

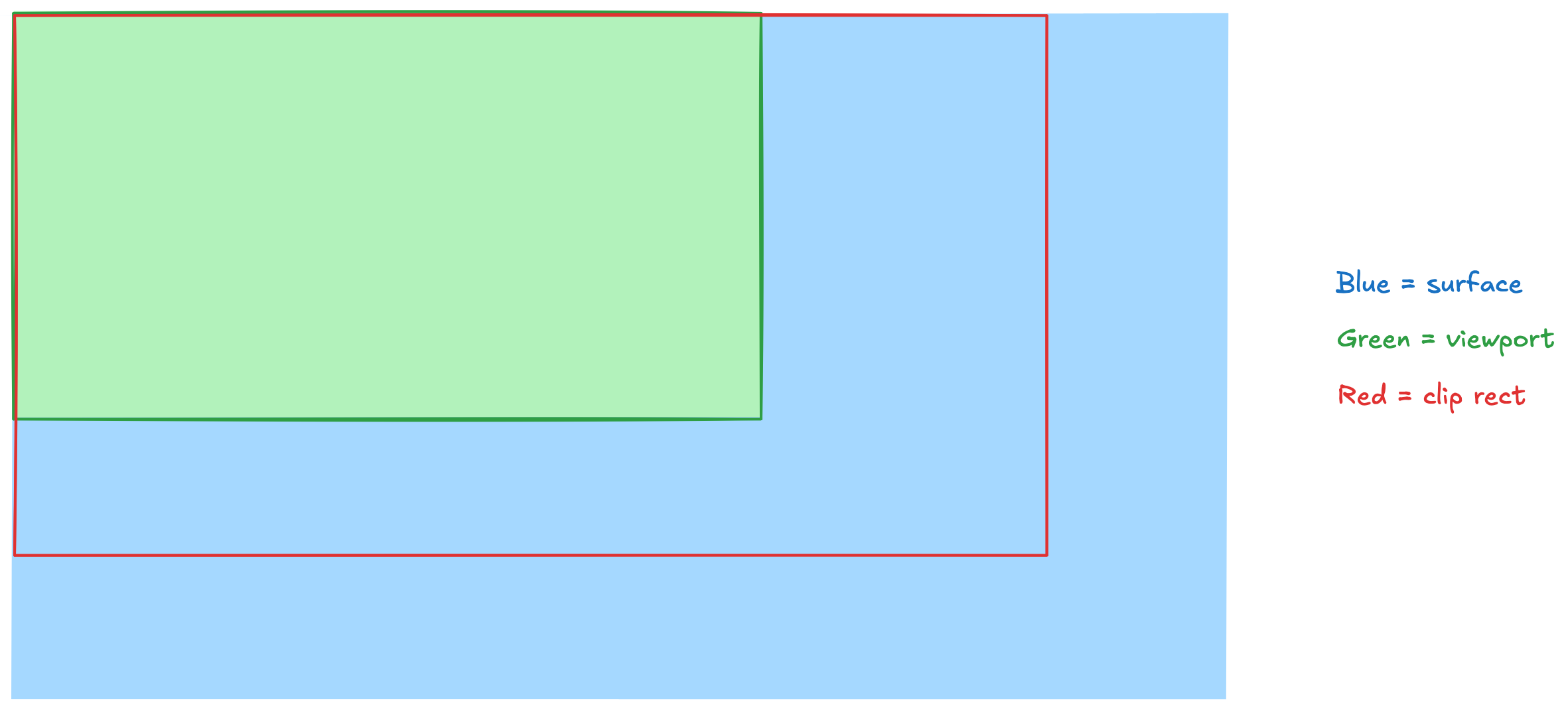

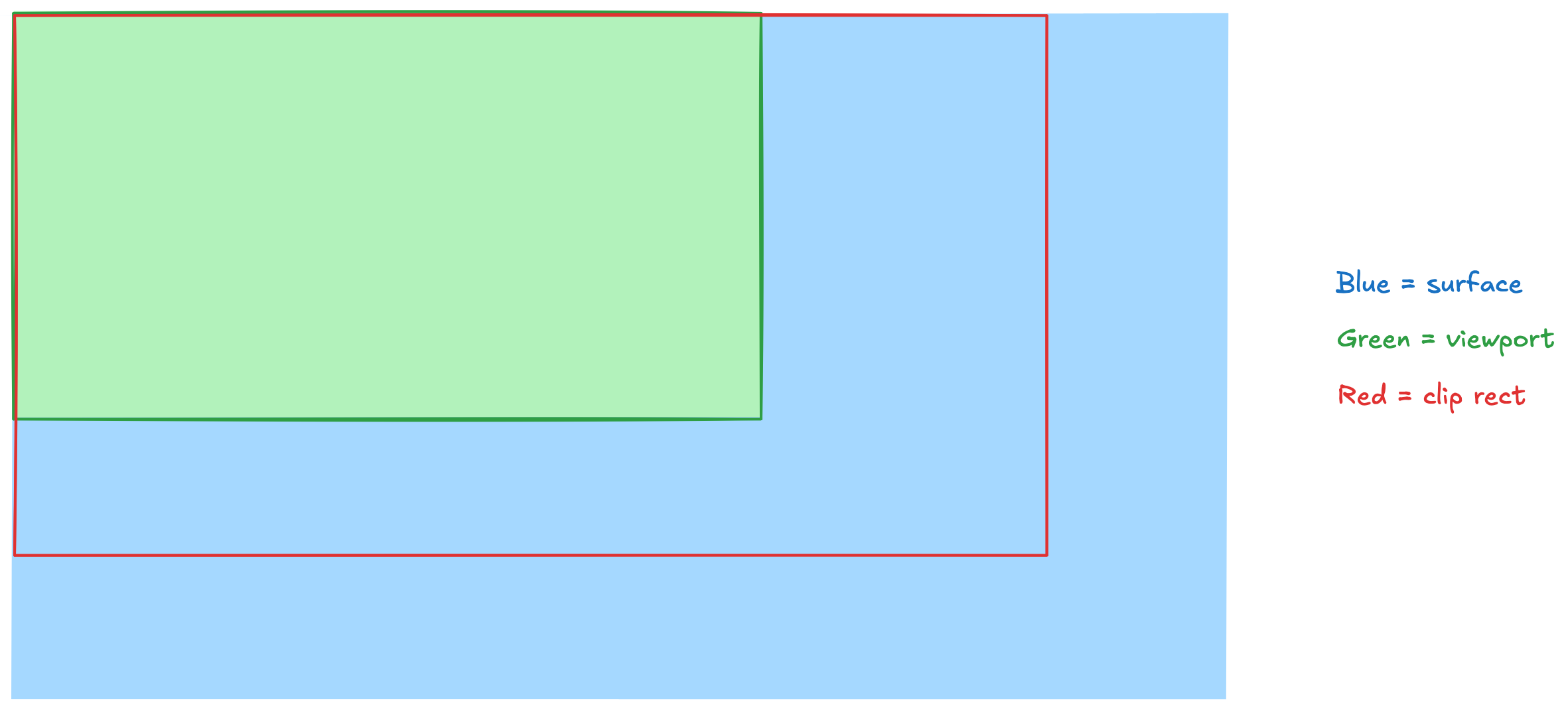

Sometimes these operations can get out of sync. For example, the clip rect might get updated before the viewport is repainted. Then we get a result like this:

We still show the old frame in the green viewport. But the clip rect has become larger and we show areas of the surface that we haven't repainted yet.

On the first resize of a window, these areas would be black. On the second resize, those areas would be filled with old pixel values. They would show whatever we had previously painted in those areas.

Similarly, in a certain edge case while making the window smaller, we would sometimes repaint the viewport before we would update the clip rect.

Then parts of the clip rect would still show the previous frame because the new frame was smaller and we did not repaint any areas beyond the new viewport.

Now why do these operations not happen in sync?

We use two different Windows APIs here:

Here's what's important to understand: both functions return synchronously on the CPU. However, they schedule tasks that run asynchronously on the GPU at a later time. Windows and its services (such as DWM) decide when these tasks will run and in which order. So they take effect asynchronously, and not always within the same frame.

Unfortunately, Windows provides no way for us to synchronize those operations. So I had to find other approaches to fix this.

There were two options that I evaluated with the Chromium maintainers:

- While resizing, paint all previously drawn areas outside of the viewport transparent. This makes those areas invisible. It fixes the artifacts.

- While resizing, switch from an

IDXGISwapChain1 to a DirectComposition surface which synchronizes updates with IDCompositionDevice::Commit. This also fixes the artifacts.

We went with the first option because it leads to faster resizes than the second option.

I landed a patch in Chromium that implemented that first solution.

I also submitted two other patches in preparation for the main patch:

- The first one fixed a bug in existing code that would make CI fail in combination with the main patch. It also made launching Electron apps and Chrome a tiny bit faster.

- The second one was split off to make code review easier on the main patch.

Second bug

In addition to this first bug, there was a second bug which also led to stale pixels.

Here's what was going on there:

When the user resizes the window, Chromium needs to redraw the contents of the window for the new window size. This takes some time. The new frame isn't ready immediately.

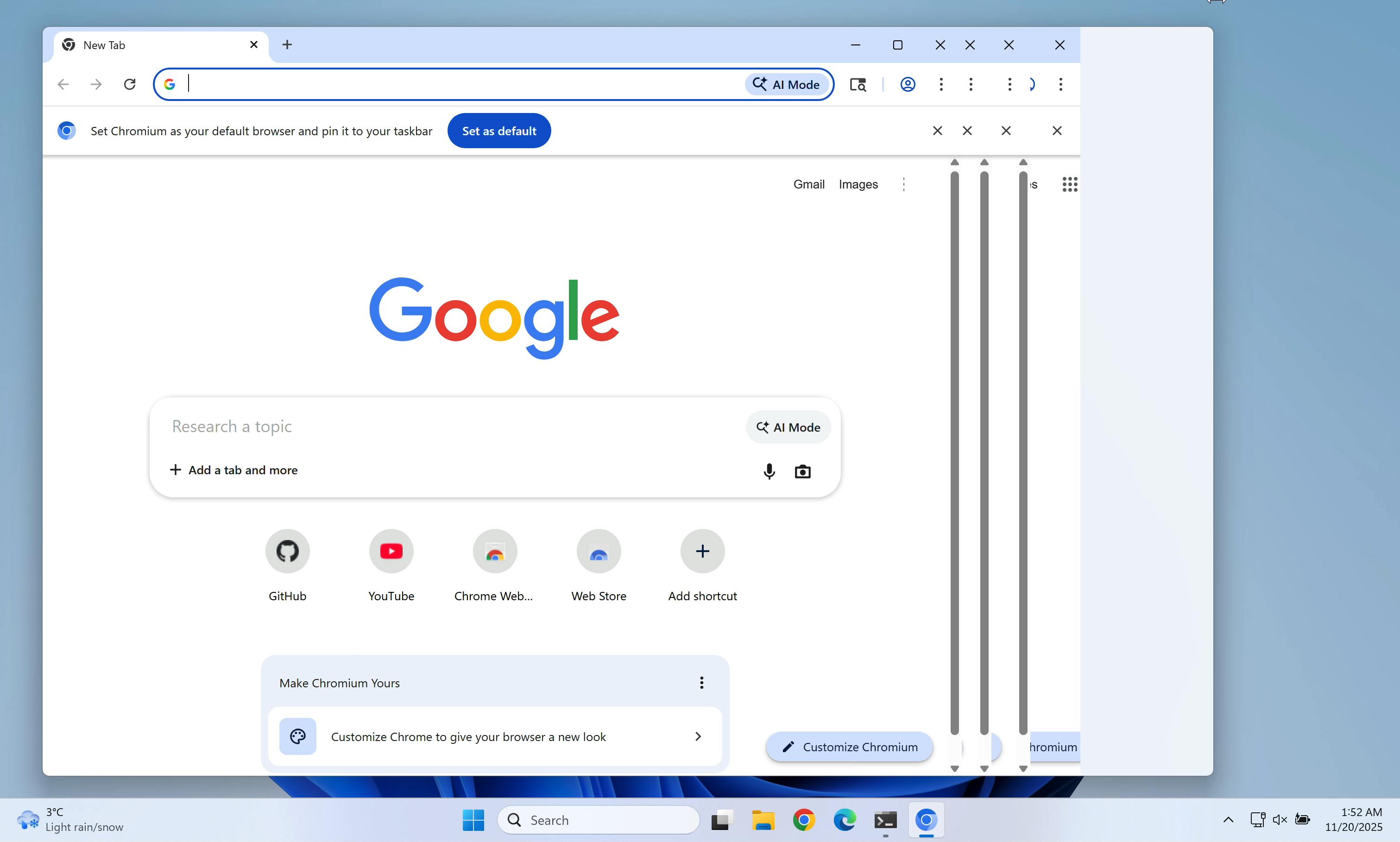

Here's a sequence of frames that demonstrates this:

At a certain time during the resize, Windows tells us: "The window is 1,000 pixels wide." But the frames that the browser compositor produces are lagging behind. The last frame that we have painted might be 600 pixels wide.

Historically, Chromium used to skip frames where the width of the window did not match the width of the frame that it last painted. It would decide to just not update the window.

However, that would often lead to the window contents not being updated at all until the resize operation was finished.

So in 2015 someone decided: "Why not show these frames? They might not match the window size perfectly, but at least we can show something."

It would lead to gutter, but at that time the gutter was black. So that was better than the previous implementation.

Now, 10 years later with DirectComposition, that gutter was often filled with stale pixels.

Let's look at what was happening there:

Every frame consists of multiple render passes. These render passes represent the various things that should be drawn on screen. From complicated bitmaps to rectangles filled with solid colors.

Every frame has a root render pass, which contains all other render passes and glues them together. (Render passes are arranged in a tree structure and the root render pass is the root of that tree.)

So now during a resize, we'd get to a point where we know the window is 1,000 pixels wide. Accordingly, we'd adjust the viewport of our output surface to also be 1,000 pixels wide. But the frame that we just received is only 600 pixels wide.

The optimization from 2015 would then go and change the width of the root render pass to also be 1,000 pixels. But it wouldn't change what the render passes would actually draw on screen. They'd still only contain instructions to draw a picture that is 600 pixels wide.

Here's what that would look like:

The yellow area is the area in which the render passes of the frame actually drew something. It's 600 pixels wide.

However, our green viewport and our red clip rect are 1,000 pixels wide. That's the area that we show on screen. (After all, the width attribute of the root render pass claimed that it would redraw the full area of 1,000 pixels.)

But because we had no draw instructions for the 400 pixels on the right, those areas didn't get updated.

On the first resize, we'd show black pixels there. (That's the color that we initialize the surface with.)

On subsequent resizes, those areas would show whatever was drawn to them before. We'd see stale pixels.

I landed a fix for this issue in crrev.com/c/7156576.

The fix changes what we do when we receive a frame with a different size than our window. Instead of resizing the frame and adding gutter that contains stale pixels, we resize our viewport and our clip rect.

We clip our surface to the size of the frame that we received. We don't show anything beyond the 600 pixels that we have draw instructions for.

Voilà, no more gutter, no more stale pixels!

Without supports_viewporter, this would be an expensive operation because it would allocate a new output surface. However, with DirectComposition, we use the "viewporter" feature. So we don't reallocate the surface when we change the viewport size. We just make a different portion of it visible. Thus, it is a cheap operation.

Backporting the patches to Electron

Once the fixes made it into Chromium, we had to pull them into Electron, too.

On the main branch, Electron updates its Chromium version constantly. As a result, the patches were merged into main in a Chromium roll PR.

However, commits that make it into main right now will only be included in an Electron release in about three months. Our existing release and pre-release branches run on older Chromium versions.

Thus, the next step was to backport the patches to Electron 39 and Electron 40.

Electron keeps a list of Chromium patches in the patches/chromium directory. When we backport a Chromium patch, we add it there. When building Electron, these patches are applied to the Chromium source code.

(In general, we try to keep the number of Chromium patches low. Every patch can lead to merge conflicts during Chromium updates. The maintenance burden from patches is real.)

The Electron 39 backport PR was merged pretty quickly. The fix became part of Electron 39.2.6. 🎉

If you resize a window on Electron 39.2.6 or later, you'll see no more stale pixels.

(The patches are also part of Google Chrome Canary. They should be part of a stable Google Chrome release in February 2026.)

Thanks

Big thanks to Plasticity for funding this work!

Thanks to Michael Tang and Vasiliy Telezhnikov from the Chromium team for their help.

Final thoughts

This was the hardest bug I have ever worked on (and I have worked on many hard bugs in 18 years of writing software).

But it was also one of the most fun projects I have ever worked on.

If you found this interesting, please consider contributing to Electron! We love seeing new faces.