Keeping up with long-form content is one of the biggest time sinks for developers and knowledge workers.

Podcasts, conference talks, and YouTube tutorials are invaluable sources of information, but a 90-minute episode demands 90 minutes of your attention.

I built a YouTube and podcast summarisation tool to solve this problem for me.

Audio Notes takes any YouTube or podcast URL and produces an AI-powered summary complete with key takeaways, action items, and topic tags.

Instead of watching an hour-long video, you read a 3-minute summary and decide whether the full content is worth your time.

In this post I walk through how the tool works, the technology behind it, and how I combine it with my AI Researcher agent to stay across new developments without drowning in content.

~

The Problem

The pace of change in AI and software development is relentless.

New frameworks ship weekly.

Conference talks pile up.

Podcast backlogs grow faster than you can listen.

The traditional options are:

- Watch everything and lose hours each day

- Skim titles and miss important content

- Rely on someone else’s summary and hope they captured what matters to you

None of these are great. I wanted a tool that could process the source material directly and surface the parts that matter.

~

How Audio Notes Works

The workflow is three steps.

1. Paste a URL

Drop in any YouTube video or podcast URL. The tool accepts public video links and extracts the audio for processing.

2. Transcribe and Summarise

The audio is sent to Azure Speech Services for batch transcription. Once the transcript is ready, OpenAI generates a structured summary using a tailored prompt. This produces:

- A concise written summary of the content

- Key takeaways pulled from the discussion

- Action items if any are mentioned

- Topic tags for quick categorisation

3. Review Insights

The summary page presents everything at a glance.

At the top, three stat cards show the original content duration, the estimated reading time for the summary, and the time saved.

For a 60-minute podcast, you typically get a summary that takes 3-4 minutes to read. That is a 90%+ time saving on every piece of content you process.

Below the stats, the full summary is rendered with markdown formatting, followed by the key takeaways, action items, and topic badges.

~

The Technology Stack

Audio Notes is built on .NET Core with the following services:

- Azure Speech Services

- OpenAI

- Azure Blob Storage

- SQL Server

- Semantic Kernel

The batch transcription pipeline runs asynchronously. You submit a URL, a background process handles the download, transcription, and file storage, and the web app polls for completion.

Once the transcript is available, summary generation takes a few seconds.

~

Combining Audio Notes with the AI Researcher Agent

This is where things get interesting.

In a previous post I described how I built an AI Researcher and Newsletter Publisher using the Microsoft Agent Framework with background responses.

That agent searches for the latest developments across blogs, GitHub repositories, and news sources, then compiles a newsletter.

I use both tools together as part of my weekly learning workflow:

- The AI Researcher agent identifies what is new and noteworthy. It surfaces blog posts, release announcements, or conference talks I should pay attention to.

- When the researcher flags a long-form video or podcast, I feed the URL into Audio Notes to get the summary.

- I scan the key takeaways and decide whether the full content warrants a deeper look.

This combination means I can process a week’s worth of AI and development news in under an hour.

The researcher agent handles breadth, telling me what exists.

Audio Notes handles depth, telling me what each piece of content actually says.

Neither tool replaces the other. Together they cover a pipeline from discovery to quick understanding

~

A Practical Example

A recent workflow looked like this.

The AI Researcher agent flagged a 6 hour Lex Fridman podcast and discussion with David Heinemeier Hansson (DHH), the creator of Ruby on Rails

Rather than blocking out time to listen, I pasted the URL into Audio Notes and within minutes I had:

- A summary of the episode

- Key and notable takeaways around hiring, software development, work-life balance and more

- Action items to consider

The summary told me everything. Total time spent: 2 minutes instead of 6 hours. In the end, I decided to listen to this podcast at another time. Maybe on a long drive.

~

Time Saved at Scale

The time savings compound quickly. If you process 5 pieces of long-form content per week, each averaging 45 minutes, that is nearly 4 hours of listening.

With Audio Notes, the same content takes roughly 20 minutes to review as summaries.

Over a month that is close to 14 hours reclaimed. The summary page makes all this visible.

Each summary shows the original duration alongside the estimated reading time and a percentage indicator of time saved.

It is a small detail, but seeing “XX% time saved” on every summary reinforces that the tool is doing its job.

~

What’s Next and Ideas

I am continuing to refine the summarisation prompts to improve the quality of key takeaways and action item extraction.

I am also exploring the possibility of batch-processing multiple URLs or entire playlists in a single operation, so the AI Researcher agent could automatically feed its discoveries into Audio Notes without manual intervention.

If you are interested in the background responses pattern that powers the AI Researcher agent, I covered the implementation in detail in the background responses post.

~

Summary

Audio Notes turns long-form video and podcast content into structured, scannable summaries.

Combined with the AI Researcher agent for content discovery, it forms a complete pipeline for staying current without the time commitment of consuming everything in full.

You can learn more about the AI Researcher in new Microsoft Agent Framework course here.

~

It’s the 73rd Day of 2026! Per my previous post, I promised updates and thus, updates delivered!

There’s a problem I’ve run into repeatedly over the years. Actually, it’s more like a pattern of problems.

I’ve got:

- notes scattered across markdown files

- lists living in some task app

- social media posts written in drafts somewhere else

- and half-finished ideas bouncing between GitHub issues, notebooks, and random documents.

Individually, each of these tools is “fine” yet fragmented and leaves ideas, messaging, and lists leaking and losing ideas to the nebulous.

That’s exactly the mess that led me to build InterlinedList.

And now it’s live:  https://interlinedlist.com

https://interlinedlist.com

What InterlinedList Actually Is

At its core, InterlinedList is a platform that ties together three things that are usually awkwardly separated:

- Lists

- Social media posting (to your other accounts too, not just on IntelinedList)

- Markdown documents

Each of these solves a different part of the “organize your thinking and output” problem. But the real value shows up when they’re connected.

InterlinedList brings them together into a single system.

Not another note app.

Not another scheduling tool.

Not another task manager.

Instead, it’s a workflow** platform for ideas that turn into posts, lists, and documents.

Lists That Connect to What You Do

Everyone has lists. They might be all over the place. With InterlinedList you can create your own lists, with whatever schema of columns you want.

Ideas lists.

Research lists.

Feature lists.

Writing queues.

Project breakdowns.

The problem is most list tools treat lists like dead data. You write them down, check things off, and that’s about it. InterlinedList treats lists more like launch points. A list item can become:

- a social media post

- a markdown document

- a reference entry

- a trackable idea

Instead of bouncing between five tools, the list becomes the center of gravity. Which is how most people actually work. Over time, my intent is to bring these features to be even more seamlessly connected. Eventually, there will even be options to bring together your LLMs you prefer to extend the capabilities of each of these things in your workflow.

Social Media Posting Without the Chaos

Posting to social platforms today usually looks like this:

- Write something somewhere

- Copy it into another platform

- Schedule it somewhere else

- Lose track of what you’ve already posted

InterlinedList brings posting directly into the workflow.

You can:

- draft posts

- schedule posts

- organize posts into lists

- connect posts to notes or markdown docs

- refer to your cross-posted posts from InterlinedList (for example, see image!)

The goal is simple: make posting part of your idea workflow instead of a disconnected chore.

The first integrations include platforms like:

- Mastodon

- Bluesky

And the idea is to keep expanding that ecosystem. More to come and also open to ideas!

Markdown Documents That Fit the Workflow

If you’re like me, markdown is where the real thinking happens.

Articles. Notes. Research. Drafts. Documentation.

But markdown tools often exist in their own isolated worlds.

InterlinedList allows you to maintain markdown documents directly alongside your lists and posts, making it possible to move naturally between: writing, organizing, and publishing.

Why These Three Things Belong Together

This was the key realization. Lists, posts, and markdown aren’t separate activities. They’re three phases of the same process:

- Capture the idea → lists

- Develop the idea → markdown

- Share the idea → social posts

Most tools treat these as unrelated workflows. InterlinedList treats them as one continuous pipeline. Which means less context switching, less tool juggling, and far fewer lost ideas.

Early Access Offer

To kick things off an early access offer, I’m doing something simple. If you’re interested in organizing ideas, posts, and documents in one place, now’s a great time to jump in.

The first 10 users who sign up will receive a full-featured subscription account for free.

No trial. No feature restrictions. Just the full platform.

Built Because I Wanted It

Like a lot of the things I’ve built, InterlinedList started as something I wanted for myself.

I needed a place where:

- research lists

- post drafts

- markdown articles

- and publishing

could actually live in the same ecosystem.

After building it and using it, the obvious next step was to open it up so others could use it too. Let me know what you think!

With that, stay tuned, the team has a lot more coming!

** I’d add that, this is absolutely a work in progress and the team will be working to bring together more of the workflow concept and features to bridge this set of tooling together to be even more seamless.

Welcome to F# Weekly,

A roundup of F# content from this past week:

News

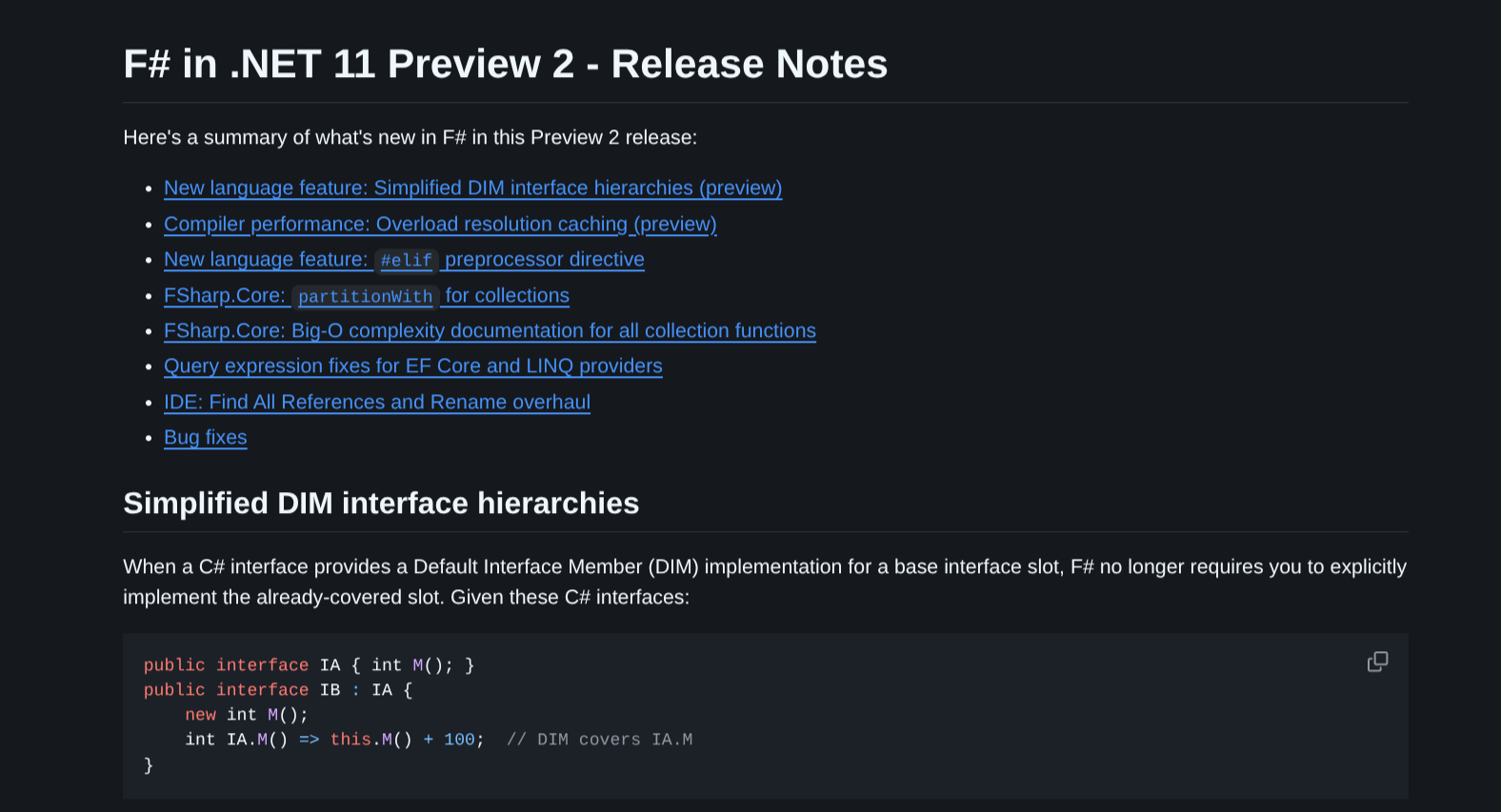

- F# in .NET 11 Preview 2 – Release Notes

- Safe Clean Architecture

- RFC: How should Fantomas handle lambda expressions that would change semantics on a single line?

Microsoft News

- .NET 11 Preview 2 is now available! – .NET Blog

- Modernize .NET Anywhere with GitHub Copilot – .NET Blog

- .NET 10.0.5 Out-of-Band Release – macOS Debugger Fix – .NET Blog

- .NET and .NET Framework March 2026 servicing releases updates – .NET Blog

- Extend your coding agent with .NET Skills – .NET Blog

- Aspire Conf is Coming! Join us Live on March 23 | Aspire Blog

- Build a real-world example with Microsoft Agent Framework, Microsoft Foundry, MCP and Aspire – Microsoft for Developers

- Announcing the Azure Skills Plugin | All things Azure

- Visual Studio Code 1.111

- Visual Studio Dev Essentials: Free, Practical Tools for Every Developer – Visual Studio Blog

Videos

- Llama.fs – YouTube

- Clef Language – WebView and Native Application Rendering – YouTube

- Blazor Community Standup – ASP.NET Core & Blazor updates in .NET 11 Preview 2 – YouTube

- .NET AI Community Standup: Real-World AI Agent Architecture in .NET – YouTube

- Demystifying Workflows with Microsoft Agent Framework – YouTube

- AI-First Mobile Development: Live Coding with Copilot and .NET MAUI – YouTube

Blogs

- Samir Parikh: Higher Order Functions in F#

- Samir Parikh: Functions in F#

- Why I Hope I Get to Write a Lot of F# in 2026 · cekrem.github.io

- PartitionWith in C# | Celso Jr

- MOTHER, Metaprogramming, and the Meta Language – Ben Copeland

Highlighted projects

- dbrattli/Fable.Actor: F# Actors for Fable and Beam

- WillEhrendreich/SageFs: Sage Mode for F# development — REPL with solution or project loading, Live Testing for FREE, Hot Reload, and session management.

- goswinr/Earcut: The fastest and smallest polygon triangulation library. Ported to F# from Mapbox

- adz/CodecMapper: High-performance, AOT-friendly serialization for F# built around explicit schemas

New Releases

- FSharp.Core 11.0.100

- Fastoch 0.11.0

- Fidelity.CloudEdge.Runtime 0.1.7

- Fidelity.CloudEdge.Management 0.1.7

- NBomber 6.3.0

- FAkka.Akka.Persistence.FSharp 1.5.62

- FSharp.Compiler.Service 43.12.201

- FSharp.Data 8.1.0

- SignalCandy 0.3.2

- SageFs 0.6.163

- Str 0.23.0

- ArrayT 0.26.0

- ResizeArrayT 0.26.0

- Earcut 3.0.21

- CodecMapper 0.1.0

- StarFederation.Datastar 1.2.1

- FSharp.Control.AsyncSeq 4.8.0

- FSharp.Formatting 22.0.0-alpha.2

- fantomas 8.0.0-alpha-007

- Fable 5.0.0-rc.3

- AgentNet 1.0.0-rc.4

That’s all for now. Have a great week.

If you want to help keep F# Weekly going, click here to jazz me with Coffee!

(@sergeytihon.com)

(@sergeytihon.com) After four months of work, the book “Safe Clean Architecture” is now complete

After four months of work, the book “Safe Clean Architecture” is now complete

Check it out online.rdeneau.gitbook.io/safe-clean-a…#fsharp #free #e-book

Check it out online.rdeneau.gitbook.io/safe-clean-a…#fsharp #free #e-book