I am sure this has been asked before but her is my design...

1) I have built an Access database application

the distribution tool has the ability to

- display a folder picker that asks the admin for the <root> (NAS< Fileserver, etc.)

- copy the Backend or database files to that selected <root>

- create a Workstation Install tool

- file copy completed

- relink frontend to backend file system

- create a shortcut link on the workstation desktop

This is a very simplified description, but I believe that it is not an unusual request.

thanks for all your assistance in advance.

SquireDude

This is a submission for the GitHub Copilot CLI Challenge

This is a submission for the GitHub Copilot CLI Challenge

What I Built

Building Content Curator: CLI + Copilot SDK

I wanted a simple but practical project to test out the Copilot SDK. I ended up creating an AI-powered CLI that uses Copilot’s agentic core along with real-time web search (via Exa AI) to generate short-form video ideas, hooks, and full scripts for Reels, YouTube Shorts, and TikTok.

Repo: github-copilot-cli-sdk-content-curator

How Content Curator Uses GitHub Copilot SDK & Exa AI

1. Initializing the Copilot Client

At the heart of the app is the CopilotService class, which manages the AI client lifecycle:

this.client = new CopilotClient(clientOptions);

await this.client.start();

await this.createSession();

-

CopilotClientconnects directly to Copilot models installed locally via the CLI. -

client.start()initializes the client, preparing it for session creation. -

createSession()sets up a streaming session with the chosen model and system prompt.

2. Session Management

Each AI session represents a continuous conversation with the Copilot model:

this.session = await this.client!.createSession({

model: this.currentModel,

streaming: true,

systemMessage: { mode: "append", content: SYSTEM_PROMPT_BASE },

});

- model – Determines which Copilot model (GPT-4o, GPT-5, Claude, etc.) powers content generation.

- streaming: true – Enables partial outputs to be sent in real time, allowing the CLI to render content as it’s being generated.

- systemMessage – Provides base instructions for the agent, ensuring that generated content matches the expected format for short-form videos.

3. Prompt Workflow

Content Curator sends structured prompts to Copilot for:

- Content generation (

/script,/ideas,/hooks) - Content refinement (

/refine) - Generating variations (

/more-variations)

Example:

const promptWithSearch = `${searchResults}

---

${basePrompt}`;

await this.sendPrompt(promptWithSearch, contentType);

- Incorporates real-time search results from Exa AI to ensure generated content is relevant and up-to-date.

- Supports topic- and platform-specific instructions, so scripts are optimized for Instagram, TikTok, or YouTube Shorts.

Using CopilotClient directly allows Content Curator to:

- Maintain persistent AI sessions with context across multiple commands.

- Stream outputs in real time, providing an interactive user experience.

- Dynamically switch models without restarting the application.

Why Choose Copilot SDK Over Generic LLM Clients?

There are several strong reasons to prefer the Copilot SDK over generic LLM clients:

- GitHub-native workflows – Direct access to repos, files, and workflows.

- Built-in agentic behavior – Conversations, tools, reasoning, and MCP support.

The kinds of apps you can build with the Copilot SDK go well beyond content curation:

- Summarizing PRs and generating release notes

- Creating learning-path threads from a repository

- Querying personal knowledge stores

- Building CLIs and custom GUIs for AI agents

Conclusion

The Copilot SDK exposes the agentic capabilities of the Copilot CLI—including planning, tool execution, and multi-turn workflows—directly in your preferred programming language. This allows you to integrate Copilot into any environment, whether you’re building:

- GUIs with AI workflows

- Personal productivity tools

- Custom internal agents for enterprise processes

Essentially, the SDK acts as an execution platform. It provides the same agentic loop that powers the Copilot CLI, while GitHub manages authentication, models, MCP servers, and streaming sessions.

You remain fully in control of what you build on top of these core capabilities.

Demo

Here's the project link - https://github.com/shivaylamba/github-copilot-cli-sdk-content-curator

Video Walkthrough - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=znmkkjpntKc

My Experience with GitHub Copilot CLI

I used GitHub Copilot CLI extensively while building this project, primarily as a thinking partner rather than just a code generator. It helped me move faster from intent to implementation by translating natural-language prompts into concrete shell commands, code snippets, and workflow suggestions directly in the terminal.

Copilot CLI was especially useful during early development and iteration. Whether it was scaffolding project structure, generating boilerplate code, debugging errors, or suggesting optimized commands, it reduced context switching between the editor, browser, and documentation. I could stay focused on the problem I was solving instead of searching for syntax or command references.

One of the biggest impacts was how it accelerated experimentation. I could quickly try alternative approaches, validate ideas, and refine implementations by asking follow-up questions in the CLI itself. This made the development process more interactive and exploratory, particularly when working with unfamiliar tools or configurations.

Overall, GitHub Copilot CLI significantly improved my productivity and flow. It didn’t replace my understanding or decision-making, but it acted as a powerful assistant that helped me write, test, and iterate faster—especially in moments where friction would normally slow development down.

Many years ago, back when I was in my early teens, I picked up an interest in math. Arguably much more superficial than it is now. My gateway drug to discovering abstract algebra was a YouTube video about the unsolvability of the quintic.

Of course, I didn’t understand shit after watching it. I think that I got lost somewhere midway the video, where the author decided that the best idea is to keep on with the “graphical” and “friendly” explanation of groups by rotating cubes or balls, and explained the rest of the concepts in this insurmountably confusing and pointless way. It must’ve sucked to be me, because every exposition of basic group theory was either that, or needless complexity galore that required much more mathematical maturity than a 13 year old could’ve spared.

When I was procrastinating working, now - give or take - 8 years later, I saw another pointless rehashing of the same topic in the same pointless logical framework. So I thought that maybe I can do a better job.

What is a group?

Suppose that you have a set. Of anything, really - potatoes, dodgeballs, whatever. Actually, who am I lying to? Just take non-negative integers smaller than 4. Call it $G$.

Now suppose that you have an action (for potatoes it could be mashing, for dodgeballs - this, for integers - addition modulo 4) that you can perform on any two elements of that set, and that action (call it $\cdot$ - like the product operator) has the following properties:

- $(a \cdot b) \cdot c = a \cdot (b \cdot c)$ for any $a, b, c \in G$ (associativity).

- There exists an element $\varepsilon \in G$ such that for any $a \in G$, $\varepsilon \cdot a = a \cdot \varepsilon = a$ (identity element).

- For any $a \in G$, there exists an element $b \in G$ such that $a \cdot b = b \cdot a = \varepsilon$ (inverse element).

From here it should also be clear that $(\cdot) : G \times G \to G$ (closure; i.e. $(\cdot)$ maps two elements of $G$ to another element of $G$). Then the pair $(G, \cdot)$ is called a group.

So in our example, $G = {0, 1, 2, 3}$ and $(\cdot)$ is addition modulo 4. The identity element is 0, because adding 0 to any number doesn’t change it. The inverse of 1 is 3, because $1 + 3 \equiv 0 \bmod 4$; the inverse of 2 is 2, because $2 + 2 \equiv 0 \bmod 4$; and the inverse of 3 is 1.

So here we discover one of the most straightforward families of groups: integers modulo $n$ form a group. Formally speaking,

$$ \mathbb{Z}_n = ({0, 1, \ldots, n-1}, +_{\bmod n}) $$

is a group for any integer $n \geq 1$.

What is this useful for? You could model a hand of a clock with it, for example. What happens when an analog clock shows 10:35 a.m. and you add 50 minutes to it? It shows 11:25 a.m. In other words, $35 + 50 \equiv 25 \bmod 60$.

Simplest example of a group is when we set $G = { \varepsilon }$, a set with a single element, and define $(\cdot)$ such that $\varepsilon \cdot \varepsilon = \varepsilon$. This group is called the trivial group.

Exercise: It easily follows that $(\mathbb{Z}, +)$ is a group. Is $(\mathbb{Z}, -)$ a group? Don’t skim over this. Try to informally prove or disprove it. Would this construction violate any of the group properties?

Bijections and the group of bijections.

A bijection is essentially a function that maps elements from one set to another in a one-to-one manner. In other words, no two elements from the first set map to the same element in the second set, and every element in the second set has a corresponding element in the first set.

For example, we can define a bijection between $\mathbb{N}$ and $\mathbb{Z}$ as follows:

$$f(n) = \begin{cases} \frac{n}{2}, & \text{if } n \text{ is even} \ -\frac{n+1}{2}, & \text{if } n \text{ is odd} \end{cases}$$

We see that $f : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{Z}$ is a bijection, because every natural number maps to a unique integer, and every integer has a corresponding natural number. We can also invert this mapping to get $f^{-1} : \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{N}$.

As another example, we can define a bijection that maps natural numbers to even natural numbers as $f(n) = 2n$. Detour: It may seem a bit illogical: after all, aren’t there more natural numbers than even natural numbers? Infinite sets are a bit tricky to reason about. In mathematics we would say that both sets have the same cardinality (because there is a bijection between them), but they have a different density (because even natural numbers are less frequent in the set of natural numbers).

Now, let’s take our newfound group powers. The group $\text{Bij}(X)$ is the group of all bijections from a set to itself, with the group operation being function composition. So $f \in \text{Bij}(X) : X \to X$ for some set $X$, and the group operation $\circ$ is defined as $(f \circ g)(x) = f(g(x))$ for any $f, g \in \text{Bij}(X)$ and $x \in X$.

Is this actually a group? Well, go and check: the function composition is associative, the identity function $\mathrm{id}(x) = x$ serves as the identity element, and every bijection has an inverse function that is also a bijection. Furthermore, if $f, g$ are bijections then so is $f \circ g$, so the closure property holds as well.

How to demonstrate this formally, axiom by axiom:

Axiom 1: Notice that for any functions $f,g,h:X\to X$ and any $x\in X$, we have: $$ ((f\circ g)\circ h)(x)=(f\circ g)(h(x))=f(g(h(x)))=f((g\circ h)(x))=(f\circ (g\circ h))(x). $$. Since the two compositions agree on every $x\in X$, $(f\circ g)\circ h=f\circ (g\circ h)$. So (more generally) composition is associative on the set of all functions from $X$ to $X$.

Axiom 2: Define $\mathrm{id}_X:X\to X$ by $\mathrm{id}_X(x)=x$. This map is bijective. For any bijective $f$ and any $x\in X$, we have $$ (\mathrm{id}_X\circ f)(x)=\mathrm{id}_X(f(x))=f(x),\quad (f\circ \mathrm{id}_X)(x)=f(\mathrm{id}_X(x))=f(x). $$ Hence $(\mathrm{id}_X)$ is an identity element.

Axiom 3: Let $f$ be a bijection. For each $y \in X$ there exists a unique $x \in X$ with $f(x) = y$. Define $f^{-1}: X \to X$ by “$f^{-1}(y) = $ the unique $x$ such that $f(x) = y$”. This is a well-defined function. Then for any $x \in X$, $f^{-1}(f(x)) = x$, so $(f^{-1} \circ f)(x) = x$, i.e. $f^{-1} \circ f = \mathrm{id}_X$. For any $y \in X$, $f(f^{-1}(y)) = y$, so $(f \circ f^{-1})(y) = y$, i.e. $f \circ f^{-1} = \mathrm{id}_X$. So $f^{-1}$ is bijective (its inverse is $f$).

Closure: This is proven by first working forwards (prove that the composition of two bijections is injective) and then backwards (prove that the composition of two bijections is surjective). You can find a trillion proofs of this online.

Homomorphisms

A homomorphism is a “structure-preserving map” between two groups. What a useless definition. Take two groups, $(G, \cdot)$ and $(H, *)$. A homomorphism from $G$ to $H$ is a function $f : G \to H$ such that for any $a, b \in G$, $f(a \cdot b) = f(a) * f(b)$.

Example: $\ln(xy) = \ln(x) + \ln(y)$ shows that the natural logarithm is a homomorphism from the multiplicative group of positive real numbers $(\mathbb{R}^+, \cdot)$ to the additive group of real numbers $(\mathbb{R}, +)$.

Important: an isomorphism is a bijective homomorphism. In other words, it’s a structure-preserving map between two groups that is also one-to-one and onto. If two structures are isomorphic, we write $G \cong H$.

Example: The groups $(\mathbb{R}^+, \cdot)$ and $(\mathbb{R}, +)$ are isomorphic via the natural logarithm function $\ln : \mathbb{R}^+ \to \mathbb{R}$, which is a bijective homomorphism (inverse function is the exponential function $\exp : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}^+$).

That’s it.

Subgroups

A subgroup is a subset of a group that is itself a group under the same operation. Formally, if $(G, \cdot)$ is a group and $H \subseteq G$, then $(H, \cdot)$ is a subgroup of $(G, \cdot)$ if:

- For any $a, b \in H$, $a \cdot b \in H$ (closure).

- There exists an element $\varepsilon \in H$ such that for any $a \in H$, $\varepsilon \cdot a = a \cdot \varepsilon = a$ (identity element).

- For any $a \in H$, there exists an element $b \in H$ such that $a \cdot b = b \cdot a = \varepsilon$ (inverse element).

- For any $a, b, c \in H$, $(a \cdot b) \cdot c = a \cdot (b \cdot c)$ (associativity).

This is tricky, because we have to maintain closure, identity, inverses, and associativity.

Example: Consider the group $(\mathbb{Z}, +)$. The set of even integers $2\mathbb{Z} = {\ldots, -4, -2, 0, 2, 4, \ldots}$ is a subgroup of $(\mathbb{Z}, +)$ because:

- The sum of any two even integers is an even integer (closure).

- The identity element 0 is an even integer (identity element).

- The inverse of any even integer is also an even integer (inverse element).

- Addition is associative for all integers, including even integers (associativity).

Cayley’s theorem.

Every group $(G,\cdot)$ is isomorphic to a subgroup of $\mathrm{Bij}(G)$, the group of bijections of $G$ under composition.

We constructively demonstrate this below. For each $a \in G$, define left multiplication by $a$ as the map $$ L_a : G \to G,\quad L_a(x)=a\cdot x . $$

Now:

- Each $L_a$ is a bijection: its inverse is $L_{a^{-1}}$.

- Composition matches multiplication: $$ L_a\circ L_b = L_{a\cdot b}. $$

- The map $\Phi:G\to\mathrm{Bij}(G)$ given by $\Phi(a)=L_a$ is a homomorphism.

- $\Phi$ is injective, since $L_a(\varepsilon)=a$.

Hence: $\Phi(G)$ is a subgroup of $\mathrm{Bij}(G)$, and $G\cong \Phi(G)$. Thus every group can be realized as a group of bijections.

Just as a simple example: Cayley’s theorem says that $\mathbb{Z}_n \cong \Phi(\mathbb{Z}_n)$ for $\Phi(a) = L_a$ where $L_a(x) = a +_{\bmod n} x$. Notice that $\Phi$ here is not our invention: The theorem demands we take each group element and turn it into a bijection of the set $\mathbb{Z}_n$ onto itself by “left multiplication” (here, addition modulo $n$). So each element k of the group becomes the function “add k”. Every group element is doing something to a set, and group multiplication is just doing those things one after another.

The image is the set of functions $$\Psi(\mathbb Z_n) = {,x\mapsto x+k \pmod n \mid k\in\mathbb Z_n,}.$$

This is a subset of $\mathrm{Bij}(\mathbb Z_n)$, and it is closed under composition: $$ (x\mapsto x+a)\circ(x\mapsto x+b) = (x\mapsto x+a+b). $$

This is about the right time to explain symmetric groups: the symmetric group on a set $X$, denoted $\textrm{Sym}(n)$ typically taking $X = {1, 2, \ldots, n}$, is the group of all bijections from $X$ to itself under composition. The order (number of contained elements) of the symmetric group $\textrm{Sym}(n)$ is $n!$, which counts the number of ways to arrange $n$ distinct elements.

See the link already? An alternative concrete rephrasing of Cayley’s theorem is that every (finite) group of order $n$ is isomorphic to a subgroup of the symmetric group $\textrm{Sym}(n)$.

Cosets

Suppose that $(G, \cdot)$ is a group and $(H, \cdot)$ is a subgroup of $(G, \cdot)$ (stated tersely as $H \le G$). For any element $g \in G$, the left coset of $H$ in $G$ with respect to $g$ is the set $gH = { g \cdot h : h \in H }$. Similarly, the right coset of $H$ in $G$ with respect to $g$ is the set $Hg = { h \cdot g : h \in H }$.

Basic facts:

- Every element of $G$ belongs to some left-coset.

- Two left-cosets are either disjoint or identical.

- All left-cosets of $H$ in $G$ have the same number of elements as $H$.

Cosets, vaguely speaking, are useful for partitioning groups. Given a group $G$ and a subgroup $H \le G$, we let:

$$ G / H = { gH : g \in G } $$

be the set of all left-cosets of $H$ in $G$. Now suppose that we wanted to turn this set into a group. For this purpose, we want to define:

$$ (gH) \cdot (kH) = (g \cdot k)H $$

However, this definition is only valid if it doesn’t depend on the choice of representatives $g$ and $k$. In other words, if $gH = g’H$ and $kH = k’H$, we need to ensure that $(g \cdot k)H = (g’ \cdot k’)H$. From $g_1H = g_2H$ we get $g_2^{-1}g_1 \in H$, and from $k_1H = k_2H$ we get $k_2^{-1}k_1 \in H$. Thus, for the operation to be well-defined, we need:

$$ (g_2 g_2’)^{-1} (g_1 g_1’) = (g_2’)^{-1} (g_2^{-1} g_1) g_1’ \in H $$

And thus we see $g_2^{-1} g_1 \in H$, but it is conjugated by $g_1’$:

$$ (g_2’)^{-1} H g_1' $$

For this product to be in $H$, we need $H$ to be invariant under conjugation by any element of $G$, i.e. $gHg^{-1} = H$ for all $g \in G$. Such subgroups are called normal subgroups (denoted $H \triangleleft G$).

So now if we augment $G/N = { gN : g \in G }$ with the operation $(gN)(kN) = (gk)N$, we get a group called the quotient group.

This is a well-defined, pretty regular, group:

- Identity: $N$

- Inverse: $(gN)^{-1} = g^{-1}N$

- Associativity inherited from $G$

This construction has a very special purpose: it is the only way groups can be simplified without losing structure.

First Isomorphism Theorem

Suppose that $f : G \to H$ is a homomorphism between two groups $(G, \cdot)$ and $(H, *)$. The kernel of $f$ is the set $\ker(f) = { g \in G : f(g) = \varepsilon_H }$, where $\varepsilon_H$ is the identity element of $H$. The image of $f$ is the set $\mathrm{im}(f) = { h \in H : h = f(g) \text{ for some } g \in G }$.

As a simple example of a kernel, consider the homomorphism $f : (\mathbb{Z}, +) \to (\mathbb{Z}_n, +_{\bmod n})$ defined by $f(k) = k \bmod n$. The kernel of this homomorphism is the set of all integers that are multiples of $n$, i.e. $\ker(f) = n\mathbb{Z} = {\ldots, -2n, -n, 0, n, 2n, \ldots}$ - because (informally) these are the integers that map to 0 in $\mathbb{Z}_n$.

We know for a fact that the kernel of a homomorphism is always a normal subgroup of the domain group. In our example, $n\mathbb{Z}$ is indeed a normal subgroup of $(\mathbb{Z}, +)$. Furthermore, $f$ is injective if and only if $\ker(f) = {\varepsilon_G}$, where $\varepsilon_G$ is the identity element of $G$.

As an example of an image, consider the same homomorphism $f : (\mathbb{Z}, +) \to (\mathbb{Z}_n, +_{\bmod n})$. The image of this homomorphism is the entire group $\mathbb{Z}_n$, i.e. $\mathrm{im}(f) = \mathbb{Z}_n$ - because every element in $\mathbb{Z}_n$ can be obtained by taking some integer modulo $n$.

The structural theorem (or the First Isomorphism Theorem) states that if $f : G \to H$ is a homomorphism, then the quotient group $G / \ker(f)$ is isomorphic to the image of $f$, i.e. $G / \ker(f) \cong \mathrm{im}(f)$.

Constuctively we can define a map $\varphi : G / \ker(f) \to \mathrm{im}(f)$ by $\varphi(g \ker(f)) = f(g)$. This map is well-defined, because if $g \ker(f) = g’ \ker(f)$, then $g’^{-1} g \in \ker(f)$, which implies that $f(g’^{-1} g) = \varepsilon_H$, and thus $f(g) = f(g’)$. The map $\varphi$ is a homomorphism, because: $$\varphi((g \ker(f))(k \ker(f))) = \varphi((gk) \ker(f)) = f(gk) = f(g) * f(k) = \varphi(g \ker(f)) * \varphi(k \ker(f)).$$ The map $\varphi$ is surjective by definition of the image, and it is injective because if $\varphi(g \ker(f)) = \varepsilon_H$, then $f(g) = \varepsilon_H$, which implies that $g \in \ker(f)$, and thus $g \ker(f) = \ker(f)$.

Intuitively: A homomorphism collapses elements of G that differ by elements of the kernel. Once you factor out exactly this redundancy, what remains is structurally identical to the image.

Going back to our example with $f : (\mathbb{Z}, +) \to (\mathbb{Z}_n, +_{\bmod n})$, we have $\ker(f) = n\mathbb{Z}$ and $\mathrm{im}(f) = \mathbb{Z}_n$. According to the First Isomorphism Theorem, we have: $$\mathbb{Z} / n\mathbb{Z} \cong \mathbb{Z}_n.$$ This means that the quotient group $\mathbb{Z} / n\mathbb{Z}$ is structurally identical to the group $\mathbb{Z}_n$, and we can give an explicit isomorphism between them: $$\varphi : \mathbb{Z} / n\mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Z}_n, \quad \varphi(k + n\mathbb{Z}) = k \bmod n.$$

It’s useful to visualize the algebraic structures at hand a little bit:

- $n\mathbb{Z}$ is the subgroup of $\mathbb{Z}$ consisting of all multiples of $n$, i.e. $n\mathbb{Z} = {\ldots, -2n, -n, 0, n, 2n, \ldots} = { nk\mid k \in \mathbb{Z} }$.

- The quotient group $\mathbb{Z} / n\mathbb{Z}$ consists of the cosets of $n\mathbb{Z}$ in $\mathbb{Z}$, i.e. $\mathbb{Z} / n\mathbb{Z} = { k + n\mathbb{Z} : k \in \mathbb{Z} }$. There are exactly $n$ distinct cosets, which can be represented by the integers $0, 1, \ldots, n-1$.

In $\mathbb{Z} / n\mathbb{Z}$, an element is not a single integer, but rather a set of integers that differ by multiples of $n$. For example, the coset $2 + n\mathbb{Z}$ includes all integers of the form $2 + kn$ for any integer $k$. Addition is defined as: $$(a + n\mathbb{Z}) + (b + n\mathbb{Z}) = (a + b) + n\mathbb{Z}.$$ Making it a group (check the propeties!).

Tying the knot.

A group $G$ is simple if it has no normal subgroups other than the trivial group ${\varepsilon}$ and itself $G$. Simple groups are like the prime numbers of group theory - they cannot be broken down into smaller, non-trivial normal subgroups.

The factorisation lets us analyse complex groups by breaking them down into simpler components. This is the essence of the Jordan-Hölder theorem. A composition series of a finite group $G$ is a sequence of subgroups:

$$ { \varepsilon } = G_0 \triangleleft G_1 \triangleleft G_2 \triangleleft \ldots \triangleleft G_n = G $$

where each $G_{i}$ is a normal subgroup of $G_{i+1}$, and the quotient groups $G_{i+1} / G_i$ are simple groups. The Jordan-Hölder theorem states that any two composition series of a finite group have the same length and the same simple quotient groups, up to isomorphism and order.

Detour: Applications of the First Isomorphism Theorem

An integer $q$ is called a quadratic residue modulo $n \in \mathbb{N}$ if it is congruent to a perfect square modulo $n$; in other words, if there exists $x \in \mathbb{Z}$ such that $x^2 \equiv q \bmod n$.

When the number $p > 2$ is prime, it has $(p-1)/2$ quadratic residues. This is a pretty elementary result in number theory, but we can also prove it elegantly using the First Isomorphism Theorem:

Let $\mathbb{Z}_p$ be the group of integers modulo $p$ under addition, and let $\mathbb{Z}_p^$ be the group of invertible elements of $\mathbb{Z}_p$ under integer multiplication (i.e. $\mathbb{Z}_p^ = {1, 2, \ldots, p-1}$). Define the group homomorphism $f : \mathbb{Z}_p^* \to \mathbb{Z}_p^$ by $f(x) = x^2 \bmod p$. The kernel of $f$ is the set of all $x \in \mathbb{Z}_p^$ such that $x^2 \equiv 1 \bmod p$, which is ${1, -1}$ (or ${1, p-1}$; both follow from the fact that $p$ is prime).

By the First Isomorphism Theorem, we have: $$\mathbb{Z}_p^* / \ker(f) \cong \mathrm{im}(f).$$ Hence: $$|\mathrm{im}(f)| = |\mathbb{Z}_p^*| / |\ker(f)| = (p-1) / 2.$$

Which concludes the proof.

It’s quite magical, so anticipate to sit with this for a while. This theorem lets us prove that if $n$ is prime and $\lambda < 1/2$, then quadratic probing will always find a vacant bucket, and furthermore, no buckets will be checked twice.

Classification of finite groups, algebraically.

A finite simple group $S$ is isomorphic to exactly one of the following:

- A cyclic group of prime order, i.e. $S \cong \mathbb{Z}_p$ for some prime $p$.

- An alternating group $A_n$ for some $n \geq 5$.

- A group of Lie type (finite groups of $\mathbb{F}_q$-rational points of simple algebraic groups over finite fields $\mathbb{F}_q$, modulo center plus twisted forms):

- Classical groups: $\mathrm{PSL}n(q)$, $\mathrm{PSp}{2n}(q)$, $\mathrm{PSU}_n(q)$, $\mathrm{P\Omega}_n^{\pm}(q)$.

- Exceptional and twisted groups: $G_2(q)$, $F_4(q)$, $E_6(q)$, $E_7(q)$, $E_8(q)$, ${}^2E_6(q)$, ${}^3D_4(q)$, ${}^2B_2(q)$, ${}^2G_2(q)$, ${}^2F_4(q)$.

- One of the 26 sporadic groups.

Every group is some gluing and extension of these (this is actually a pretty impressive result!).

Alternating groups.

Not really super related to our topic, but alternating groups kind of interesting. Recall that $\mathrm{Sym}(n)$ is the group of all bijections of the set ${1,2,\dots,n}$, with group operation given by composition.

There exists a surjective group homomorphism $$\Psi : \mathrm{Sym}(n) \longrightarrow \mathbb{Z}_2$$ whose kernel has index 2 (the kernel is half the size of $\mathrm{Sym}(n)$). We do not need to construct $\Psi$ explicitly; its existence is a theorem.

We define the alternating group $A_n$ to be exactly this kernel:

$$ A_n := \ker(\Psi) $$

By general group theory we notice that:

- $A_n \triangleleft \mathrm{Sym}(n)$ (normal subgroup).

- $[\mathrm{Sym}(n) : A_n] = 2$ (index 2).

- $|A_n| = n! / 2$ (order).

- Finally, per the First Isomorphism Theorem, we have $ \mathrm{Sym}(n) / A_n \cong \mathbb{Z}_2 $ - important!

The unremarkable cases are as follows:

$A_1$ is the trivial group; we see that definitionally $\mathrm{Sym}(1) = {\varepsilon}$, so $A_1 = {\varepsilon}$.

$A_2$ is also the trivial group; $\mathrm{Sym}(2) \cong \mathbb{Z}_2$, so $A_2 = \ker(\Psi) = {\varepsilon}$.

$A_3$ is isomorphic to $\mathbb{Z}_3$; $\mathrm{Sym}(3)$ has 6 elements, so $A_3$ has 3 elements. It can be verified that $A_3 \cong \mathbb{Z}_3$.

To explain $A_4$, we must first expose Lagrange’s theorem and Cauchy’s theorem. Lagrange’s theorem states that for any finite group $G$ and any subgroup $H \le G$, the order of $H$ divides the order of $G$. In other words, $|G| = [G : H] \cdot |H|$, where $[G : H]$ is the index of $H$ in $G$ (the number of distinct left cosets of $H$ in $G$).

The proof of Lagrange’s theorem is straightforward: the left cosets of $H$ in $G$ partition the group $G$ into disjoint subsets, each of size $|H|$. Therefore, the total number of elements in $G$ is equal to the number of left cosets multiplied by the size of each coset, which gives us $|G| = [G : H] \cdot |H|$. From this equation, it follows that $|H|$ divides $|G|$.

Cauchy’s theorem states that if $G$ is a finite group and $p$ is a prime number that divides the order of $G$, then $G$ contains an element of order $p$. Consequently, $G$ also contains a subgroup of order $p$. We will adjourn the proof of this for later, because it’s a little involved.

Now, $A_4$ has 12 elements. By Lagrange’s theorem, the possible orders of subgroups of $A_4$ are 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 12.

To decide which of these orders actually occur, we will use Cauchy’s theorem: $2 \mid 12$, so there exists $x \in A_4$ such that $x^2 = \varepsilon$. Pick $x$ as such element. Then, ${\varepsilon, x} \le A_4$ is such a subgroup of order 2.

If the group had one element of order 2, then the subgroup would be normal and the quotient would have order 6, which is impossible because $A_4 \le \mathrm{Sym}(4)$. If there were more than three such elements, then their pairwise disjointness would imply that $A_4$ has more than 12 elements. Therefore, there are exactly three elements of order 2 in $A_4$, which we can denote as $x$, $y$, and $z$.

Now we can form the subgroup: $H = {\varepsilon, x, y, z} \le A_4$ where $x, y, z$ are the three elements of order 2. Inverses are automatic, closure holds because the product of any two elements of order 2 is the third element of order 2 (e.g., $xy = z$), and the identity element is included; further the associativity is inherited from $A_4$.

As a direct result, we see that the quotient group $A_4 / H$ has order 3. We can prove that $\mathrm Sym(A_4 / H) \cong \mathrm Sym(3)$ (exercise for the reader). Taking the kernel of the action $K = \ker(\Phi : A_4 \to \mathrm{Sym}(A_4 / H))$, we see that $K \triangleleft A_4$ and $[A_4 : K] \mid 6$ (Lagrange’s theorem). Since $[A_4 : H] = 3$, then $|A_4| = 3|H|$. Since $K \subseteq H$, $[A_4 : K] = [A_4 : H][H : K] = 3[H : K]$, so $[A_4 : K]$ is either 3 or 6. If it were 6, then this would give a subgroup of order 2 in $\mathrm{Sym}(3)$ arising as a quotient of $H$, which is impossible because the image of $H$ under the action must fix a coset. Hence $[A_4 : K] = 3$, so $[H : K] = 1$ and therefore $K = H$. Since $\mathrm{ker}(\Phi)$ is normal in $A_4$, we have shown that $H \triangleleft A_4$.

This is enough to conclude via the first isomorphism theorem that $A_4 / H \cong \mathbb{Z}_3$, giving us a non-trivial normal subgroup $H$ of $A_4$ that proves that $A_4$ is not simple.

As a side note, $H$ here is the Klein four-group, often denoted $V_4$ or just $V$. It is isomorphic to the direct product $\mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2$.

Starting with $A_5$, the alternating groups become simple. One stanard presentation is as follows:

$$ A_5 \cong \langle x, y \mid x^2 = y^3 = (xy)^5 = \varepsilon \rangle $$

This means that $A_5$ is generated by two elements $x$ and $y$ with the relations $x^2 = \varepsilon$, $y^3 = \varepsilon$, and $(xy)^5 = \varepsilon$.

Via Cayley’s theorem we let $G = A_5$ act on itself by left-multiplication. This gives a homomorphism $\Phi : A_5 \to \mathrm{Sym}(A_5)$ defined by $\Phi(g)(h) = gh$ for all $g, h \in A_5$. Since $A_5$ has 60 elements, $\mathrm{Sym}(A_5)$ is isomorphic to $\mathrm{Sym}(60)$.

The characterisaton of these groups for $n \geq 5$ is hard as heck, and I don’t know how to do this myself. So we will just leave it at that: for $n \geq 5$, the alternating group $A_n$ is simple.

Detour: Burnside’s lemma

The amount of binary sequences of length $n \geq 1$ distinct under cyclic shift is given by:

$$ a(n) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{k=1}^{n-1} 2^{\gcd(n,k)} $$

This is super useful when analysing cyclic redundancy codes, like CRC-32 (who knew?).

A cyclic shift is a permutation of the vector $x = (x_0, x_1, \ldots, x_{n-1})$ to the vector $(x_{n-1}, x_0, x_1, \ldots, x_{n-2})$. Cyclic codes (parent family of CRC-32 and others) are defined in such a way that the code is invariant under cyclic shifts, i.e. if $x$ is a codeword, then so is any cyclic shift of $x$. We will avoid talking too much about that because it requires leaping to a different river of a topic (polynomial rings over finite fields).

Anyway, how come this formula works? A group $G$ is cyclic if there exists an element $g \in G$ such that $$ G = \langle g \rangle = { g^k : k \in \mathbb{Z} }. $$ The cyclic group of order $n$ is $$ C_n = \langle r \rangle = { \varepsilon, r, r^2, \dots, r^{n-1} }, \qquad r^n = \varepsilon. $$ Further, let the group $G$ act on a set $X$. For any element $x$, the orbit of $x$ is the subset: $$ \mathrm{Orb}(x) = { g \cdot x : g \in G } \subseteq X. $$ In other words: the orbit of $x$ is the set of all elements of $X$ that can be reached by applying elements of $G$ to $x$.

Let $X = {0,1}^n$ be the set of binary strings of length $n$. Define an action of $C_n$ on $X$ by letting the generator $r$ act as a one-step cyclic rotation: $$ r \cdot (x_0 x_1 \dots x_{n-1}) = (x_{n-1} x_0 x_1 \dots x_{n-2}). $$ Then $r^k$ acts as rotation by $k$ positions, and $r^n = \varepsilon$ acts trivially.

Two strings are equivalent under cyclic shift if and only if they lie in the same orbit of this action. Hence the number of distinct binary sequences under cyclic shift is $$ a(n) = |X / C_n| $$ the number of orbits (binary necklaces).

Burnside’s lemma says that for a finite group action $G \to X$, $$ |X/G| = \frac{1}{|G|} \sum_{g \in G} |\mathrm{Fix}(g)|, $$ where $$ \mathrm{Fix}(g) = { x \in X : g \cdot x = x }. $$

Applying this to $C_n$ over $X$, we obtain $$ a(n) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} |\mathrm{Fix}(r^k)|. $$

Thus it remains to compute $|\mathrm{Fix}(r^k)|$.

Fix $k \in {0,1,\dots,n-1}$. A string $$ x = (x_0, x_1, \dots, x_{n-1}) $$ is fixed by $r^k$ if and only if $$ x_i = x_{i+k \bmod n} \quad \text{for all } i. $$

Thus the indices ${0,1,\dots,n-1}$ are partitioned into cycles under the permutation $$ i \longmapsto i + k \pmod n, $$ and the string must be constant on each cycle.

Let $d = \gcd(n,k)$. Consider the cycle containing $0$: $$ 0,, k,, 2k,, 3k,, \dots \pmod n. $$ Its length is the smallest $t>0$ such that $$ tk \equiv 0 \pmod n. $$

Write $n = dn’$, $k = dk’$ with $\gcd(n’,k’) = 1$. Then $$ tk \equiv 0 \pmod n \iff tdk’ \equiv 0 \pmod{dn’} \iff tk’ \equiv 0 \pmod{n’}. $$ Since $\gcd(k’,n’) = 1$, this holds if and only if $n’ \mid t$. Hence the minimal such $t$ is $$ t = n’ = \frac{n}{d}. $$

Therefore:

- each cycle has length $n/d$,

- the total number of cycles is $$ \frac{n}{n/d} = d = \gcd(n,k). $$

On each cycle, all bits must agree, but different cycles may be chosen independently. Hence $$ |\mathrm{Fix}(r^k)| = 2^{\gcd(n,k)}. $$

Finally we substitute into Burnside’s lemma: $$ a(n) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} 2^{\gcd(n,k)}. $$

This completes the proof.

Burnside’s lemma (also seldom called Cauchy-Frobenius lemma) follows by noticing the following (as givne by Ben Lynn in Polya Theory):

Let the orbits $X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_k$ be the partition of $X$ under the action of $G$. Observe that the resulting sets $\mathrm{Fix}_{X_k}(g)$ for $k \le n$ also partition $\mathrm{Fix}(g)$. As such, we have:

$$ \begin{aligned} \sum_{g \in G} |\mathrm{Fix}(g)| &= \sum_{g \in G} \sum_{i=1}^k |\mathrm{Fix}_{X_i}(g)| \ &= |{(g,x)\mid g \in G, x \in \mathrm{Fix}_{X_i}(g)}| \ &= \sum_{i=1}^k \sum_{g \in G} |G_x| \end{aligned} $$

By the orbit-stabiliser theorem and Lagrange’s theorem, we have $|G| = |G_x| \cdot |\mathrm{Orb}(x)|$, and hence the result follows.

Extra reading:

- Cauchy’s theorem (partial converse to Lagrange’s theorem)

- Sylow theorems (existence of subgroups of order $p^k$)

- Orbit-stabilizer theorem; isotropy groups (here $G_x$).

Solvable groups

It’s a little late to introduce this, but an Abelian group is a special type of a group where the group operation is commutative, i.e. for any $a, b \in G$, $a \cdot b = b \cdot a$. That’s just an additional axiom on top of the group axioms.

We call a finite group $G$ solvable if there exists a finite sequence of subgroups: $${ \varepsilon } = G_0 \triangleleft G_1 \triangleleft G_2 \triangleleft \ldots \triangleleft G_n = G$$ such that each $G_{i}$ is a normal subgroup of $G_{i+1}$, and the quotient groups $G_{i+1} / G_i$ are Abelian groups. Equivalently, all (simple) composition factors of $G$ are cyclic groups of prime order.

There’s two immediate facts that we will state without proof:

- If $G$ is solvable, then every subgroup and every quotient group of $G$ is also solvable.

- If $N \triangleleft G$ is a normal subgroup such that both $N$ and $G/N$ are solvable, then $G$ is also solvable.

Part 2

Fields, automorphisms, Galois groups, extensions, fundamental theorem of Galois theory, solvability by radicals. One day.

Artificial intelligence has already transformed the way organizations analyze data, predict outcomes, and generate content. The next leap forward is arriving fast. Enter agentic AI: Autonomous systems capable of reasoning, deciding, acting, and continuously improving with minimal human intervention.

Unlike predictive or generative AI, agentic AI systems don’t just support decisions; they execute them. They can start workflows, coordinate across systems, adapt to changing conditions, and optimize processes in real time. But as promising as this shift is, one foundational question often gets overlooked:

How do autonomous agents safely and reliably interact with the enterprise systems where business happens?

The answer is integration, and how organizations choose to approach it will shape the success or failure of agentic AI initiatives.

Why integration is the real enabler of agentic AI

Agentic AI cannot exist in isolation. An agent is only as capable as the data, systems, and processes it can access and orchestrate.

A helpful analogy is the difference between a compass and a GPS. A compass provides direction, much like traditional AI delivers insights. A GPS, however, combines maps, traffic data, and real-time signals to guide action. Agentic AI works the same way: Autonomy emerges only when intelligence is paired with deep, trusted connectivity across the enterprise.

To operate autonomously, AI agents must be able to:

- Access high-quality, contextual data across systems.

- Navigate fragmented, hybrid IT landscapes.

- Trigger and coordinate actions across applications.

- Operate within defined governance, security, and compliance boundaries.

These requirements elevate integration from a technical concern to a strategic business capability.

The integration spectrum: Different ways to feed data to agents

Organizations exploring agentic AI quickly discover that there is no single way to connect agents to enterprise systems. Instead, there is a spectrum of integration approaches, each with trade-offs.

At one end are direct API connections and straight-through integrations, where agents call services or databases directly. This approach can work well for narrow use cases or greenfield environments, but it often struggles with scalability, error handling, and governance as complexity grows.

Others turn to open source integration frameworks or event streaming platforms, which provide flexibility and strong developer control. These options can be powerful, especially for digitally native teams, but they typically require significant engineering effort to manage security, life cycle management, monitoring, and enterprise-grade operations.

Many organizations adopt integration platforms or integration platform as a service (iPaaS) solutions, which abstract connectivity, orchestration, and transformation logic into reusable services. These platforms are increasingly adding AI-assisted features — such as automated mapping, testing, and monitoring — to reduce manual effort.

Finally, large enterprises often look for deeply embedded integration platforms that are tightly aligned with their core business applications, data models, and process frameworks. These solutions emphasize governance, scalability, and business context, which are critical when agents may act autonomously.

Choosing the right approach depends on factors such as organizational maturity, regulatory requirements, landscape complexity, and the level of autonomy desired.

Why agentic AI cannot scale without an integration strategy

Most enterprises operate across a mix of cloud services, on-premises systems, partner networks, and industry-specific applications. Data is fragmented, processes span multiple systems, and change is constant.

Without a strong integration foundation, agentic AI initiatives face genuine risks:

- Agents acting on incomplete or inconsistent data.

- Brittle automations that fail at scale.

- Limited visibility into decisions and actions.

- Governance gaps that undermine trust and compliance.

Organizations that treat integration as a strategic capability, rather than a project-by-project necessity, are better positioned to scale agentic AI safely. They gain the ability to automate end-to-end processes, adapt quickly to change, and continuously optimize operations, turning autonomy into a competitive advantage rather than a liability.

The rise of agentic integration

As agentic AI grows, integration itself is becoming more autonomous.

Across the market, we’re seeing early examples of agentic integration patterns, where AI assists, or increasingly automates, parts of the integration lifecycle:

- Discovering systems, APIs, and events.

- Designing and mapping integrations based on intent.

- Deploying and testing integration flows.

- Monitoring, optimizing, and even “healing” failures.

In this model, integration experts shift from hands-on builders to strategic orchestrators, defining policies, outcomes, and guardrails while agents handle execution. This mirrors trends in other domains, from Infrastructure as Code to autonomous operations.

Positioning enterprise integration platforms in an agentic world

Enterprise-grade integration platforms are evolving to meet this shift by combining:

- Support for multiple integration styles (API-led, event-driven, B2B, A2A).

- AI-assisted design, mapping, and monitoring.

- Built-in security, governance, and life cycle management.

- Connectivity across systems.

These platforms, such as SAP Integration Suite, sit at this end of the spectrum, focusing on scalability, trust, and business context. By embedding AI capabilities directly into integration workflows and aligning closely with enterprise business processes, these platforms aim to make agentic AI operationally viable at scale, not just technically possible.

For organizations already running complex, regulated, or mission-critical landscapes, this approach can reduce risk, speed time to value, and provide the governance needed when autonomous agents begin to act on behalf of the business.

Looking ahead: How autonomous should integration become?

Agentic AI represents a fundamental shift in the way businesses design and run their operations. But autonomy is not binary; it’s a continuum.

Just as autonomous driving systems range from driver assistance to full self-driving, integration platforms will develop along a spectrum of autonomy. The key question for enterprises is not if integration should become more autonomous, but how much autonomy they are ready to trust, and where.

Organizations that start building this foundation now — by modernizing integration, clarifying governance, and experimenting with agentic patterns — will be best positioned to shape the next era of autonomous business.

The future of agentic AI will be defined not only by smarter models, but by smarter connections.

The post Agentic AI meets integration: The next frontier appeared first on The New Stack.

Customizing Docker Hardened Images

In Part 1 and Part 2, we established the baseline. You migrated a service to a Docker Hardened Image (DHI), witnessed the vulnerability count drop to zero, and verified the cryptographic signatures and SLSA provenance that make DHI a compliant foundation.

But no matter how secure a base image is, it is useless if you can’t run your application on it. This brings us to the most common question engineers ask during a DHI trial: what if I need a custom image?

Hardened images are minimal by design. They lack package managers (apt, apk, yum), utilities (wget, curl), and even shells like bash or sh. This is a security feature: if a bad actor breaks into your container, they find an empty toolbox.

However, developers often need these tools during setup. You might need to install a monitoring agent, a custom CA certificate, or a specific library.

In this final part of our series, we will cover the two strategies for customizing DHI: the Docker Hub UI (for platform teams creating “Golden Images”) and the multi-stage build pattern (for developers building applications).

Option 1: The Golden Image (Docker Hub UI)

If you are a Platform or DevOps Engineer, your goal is likely to provide a “blessed” base image for your internal teams. For example, you might want a standard Node.js image that always includes your corporate root CA certificate and your security logging agent.The Docker Hub UI is the preferred path for this. The strongest argument for using the Hub UI is maintenance automation.

The Killer Feature: Automatic Rebuilds

When you customize an image via the UI, Docker understands the relationship between your custom layers and the hardened base. If Docker releases a patch for the underlying DHI base image (e.g., a fix in glibc or openssl), Docker Hub automatically rebuilds your custom image.

You don’t need to trigger a CI pipeline. You don’t need to monitor CVE feeds. The platform handles the patching and rebuilding, ensuring your “Golden Image” is always compliant with the latest security standards.

How It Works

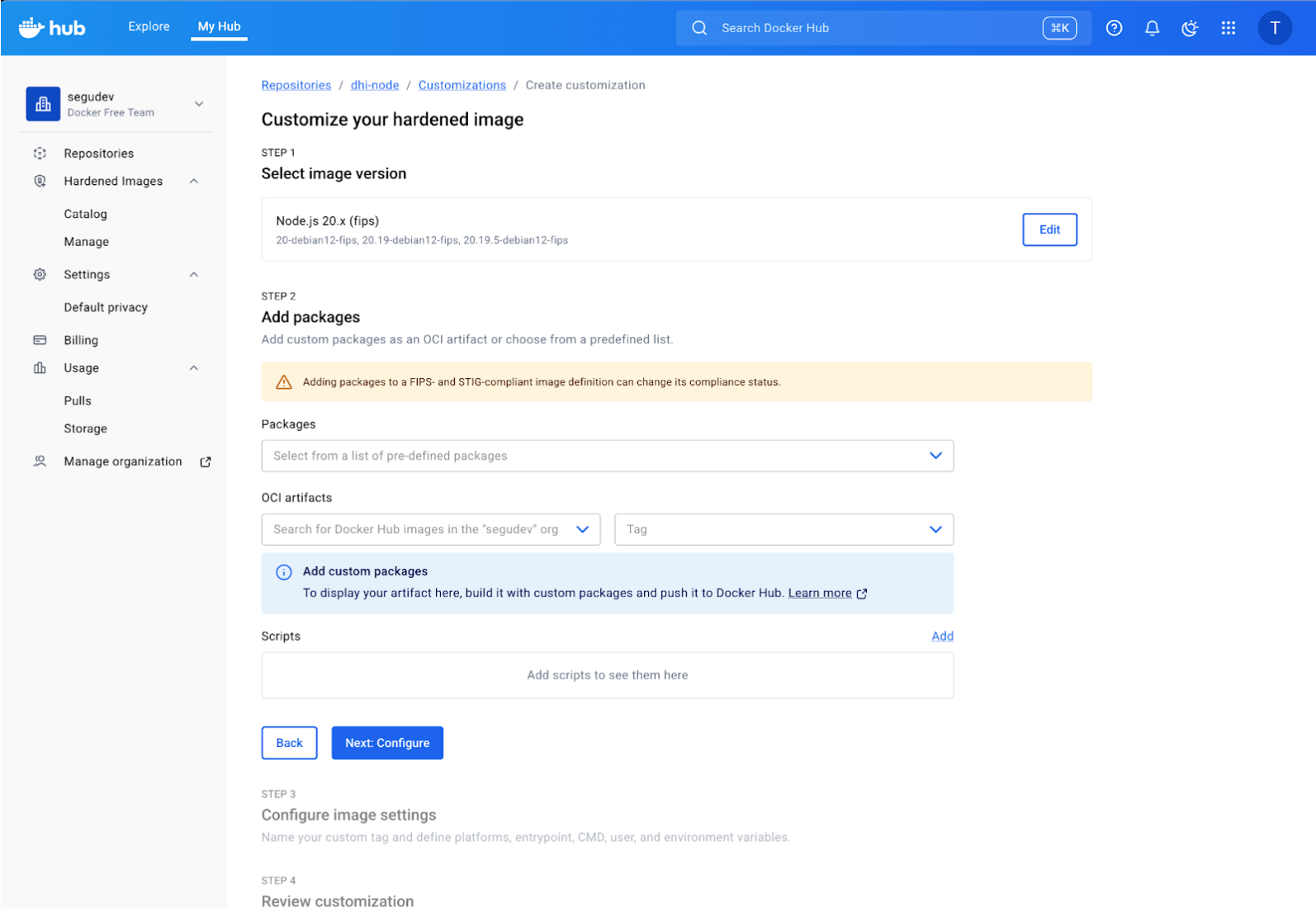

Since you have an Organization setup for this trial, you can explore this directly in Docker Hub.First, navigate to Repositories in your organization dashboard. Locate the image you want to customize (e.g., dhi-node), then the Customizations tab and click the “Create customization” action. This initiates a customization workflow as follows:

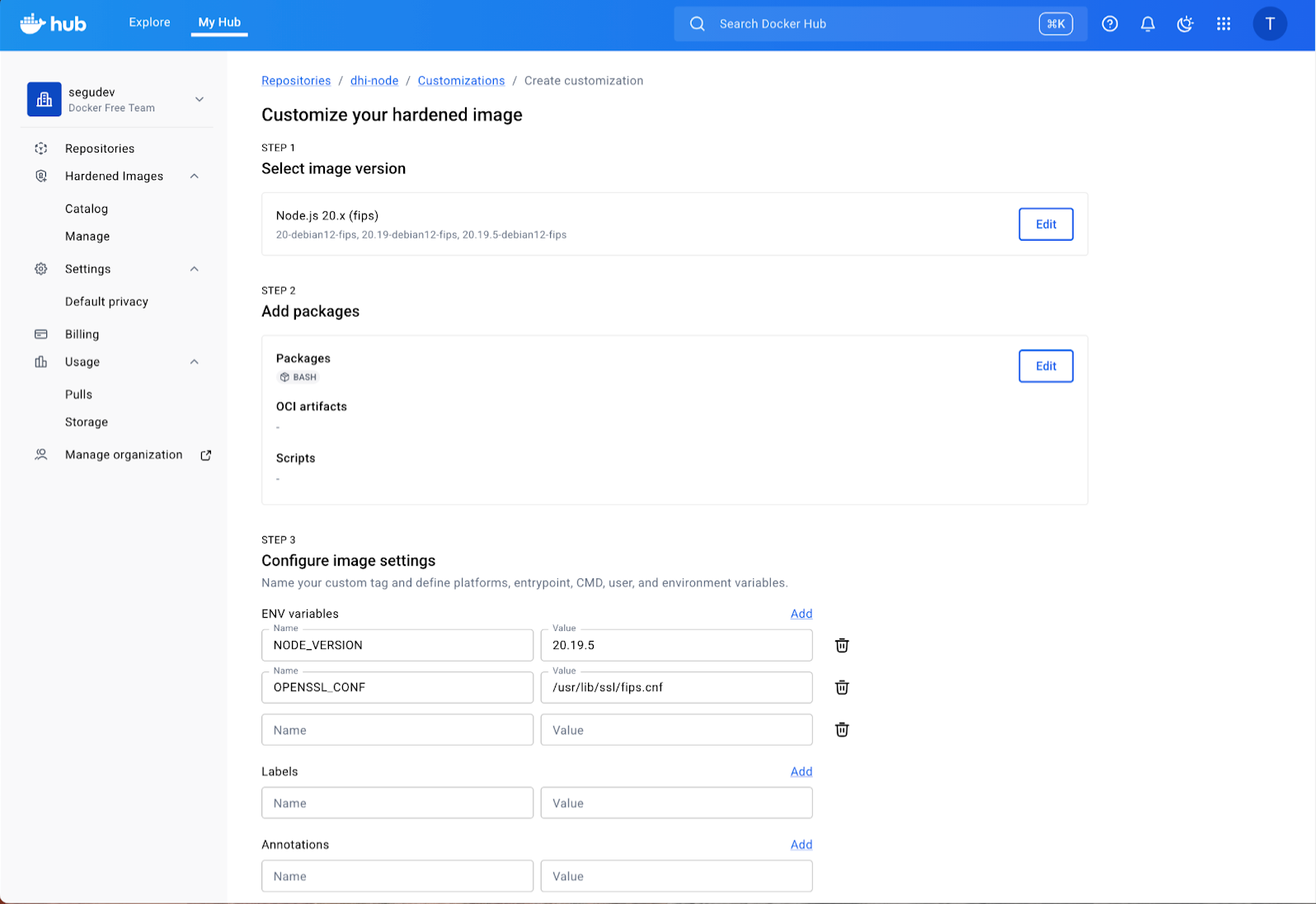

In the “Add packages” section, you can search for and select OS packages directly from the distribution’s repository. For example, here we are adding bash to the image for debugging purposes. You can also add “OCI Artifacts” to inject custom files like certificates or agents.

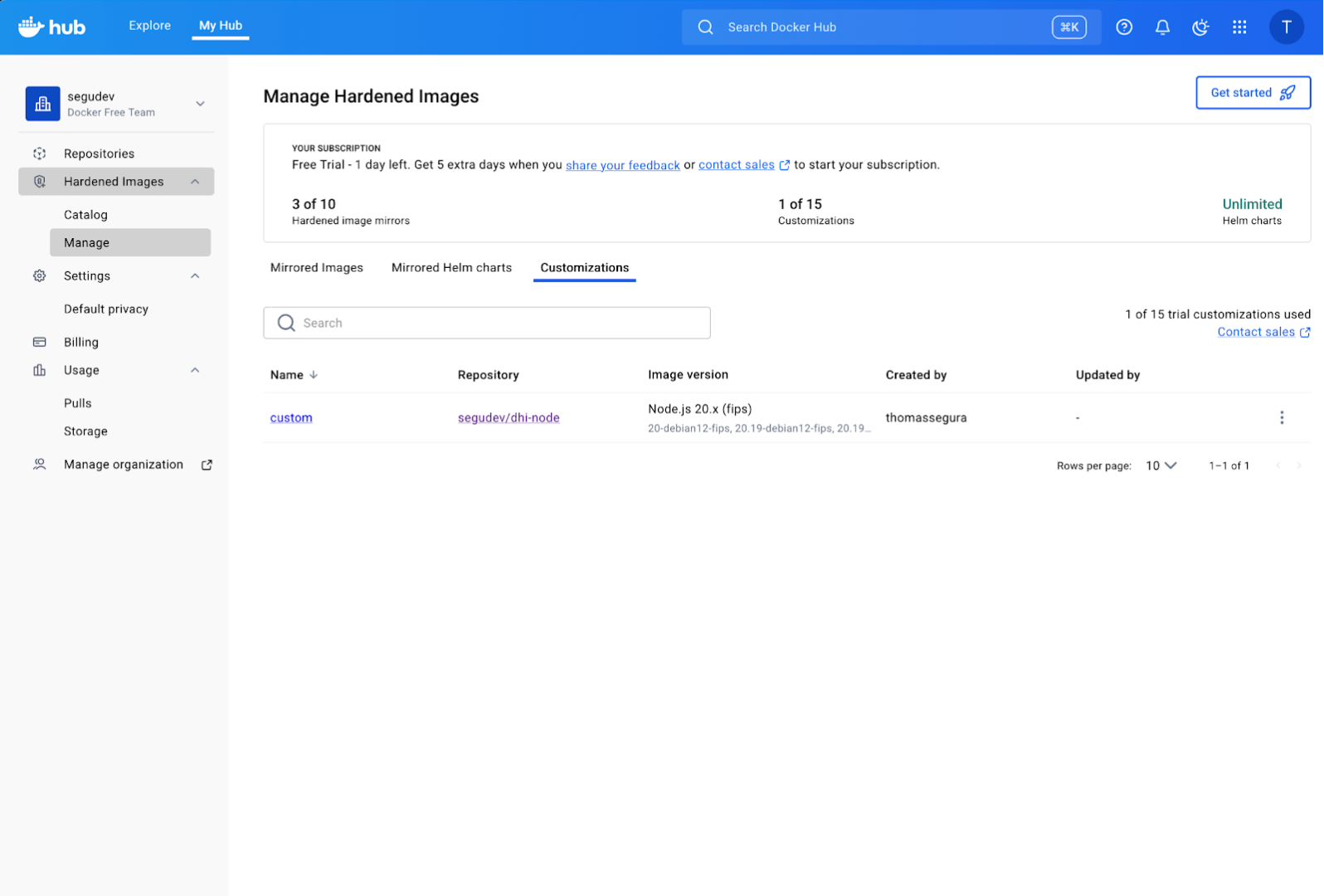

Finally, configure the runtime settings (User, Environment Variables) and review your build. Docker Hub will verify the configuration and queue the build. Once complete, this image will be available in your organization’s private registry and will automatically rebuild whenever the base DHI image is updated.

This option is best suited for creating standardized “golden” base images that are used across the entire organization. The primary advantage is zero-maintenance security patching due to automatic rebuilds by Docker Hub. However, it is less flexible for rapid, application-specific iteration by individual development teams.

Option 2: Multi-Stage Build

If you are an developper, you likely define your environment in a Dockerfile that lives alongside your code. You need flexibility, and you need it to work locally on your machine.

Since DHI images don’t have apt-get or curl, you cannot simply RUN apt-get install my-lib in your Dockerfile. It will fail.

Instead, we use the multi-stage build pattern. The concept is simple:

- Stage 1 (Builder): Use a standard “fat” image (like debian:bookworm-slim) to download, compile, and prepare your dependencies.

- Stage 2 (Runtime): Copy only the resulting artifacts into the pristine DHI base.

This keeps your final image minimal, non-root, and secure, while still allowing you to install whatever you need.

Hands-on Tutorial: Adding a Monitoring Agent

Let’s try this locally. We will simulate a common real-world scenario: adding the Datadog APM library (dd-trace) globally to a Node.js DHI image.

1. Setup

Create a new directory for this test and add a simple server.js file. This script attempts to load the dd-trace library to verify our installation.

app/server.js

// Simple Express server to demonstrate DHI customization

console.log('Node.js version:', process.version);

try {

require('dd-trace');

console.log('dd-trace module loaded successfully!');

} catch (e) {

console.error('Failed to load dd-trace:', e.message);

process.exit(1);

}

console.log('Running as UID:', process.getuid(), 'GID:', process.getgid());

console.log('DHI customization test successful!');

2. Hardened Dockerfile

Now, create the Dockerfile. We will use a standard Debian image to install the library, and then copy it to our DHI Node.js image. Create a new directory for this test and add a simple server.js file. This script attempts to load the dd-trace library to verify our installation.

# Stage 1: Builder - a standard Debian Slim image that has apt, curl, and full shell access.

FROM debian:bookworm-slim AS builder

# Install Node.js (matching our target version) and tools

RUN apt-get update && \

apt-get install -y curl && \

curl -fsSL https://deb.nodesource.com/setup_24.x | bash - && \

apt-get install -y nodejs

# Install Datadog APM agent globally (we force the install prefix to /usr/local so we know exactly where files go)

RUN npm config set prefix /usr/local && \

npm install -g dd-trace@5.0.0

# Stage 2: Runtime - we switch to the Docker Hardened Image.

FROM <your-org-namespace>/dhi-node:24.11-debian13-fips

# Copy only the required library from the builder stage

COPY --from=builder /usr/local/lib/node_modules/dd-trace /usr/local/lib/node_modules/dd-trace

# Environment Configuration

# DHI images are strict. We must explicitly tell Node where to find global modules.

ENV NODE_PATH=/usr/local/lib/node_modules

# Copy application code

COPY app/ /app/

WORKDIR /app

# DHI Best Practice: Use the exec form (["node", ...])

# because there is no shell to process strings.

CMD ["node", "server.js"]

3. Build and Run

Build the custom image:

docker build -t dhi-monitoring-test .

Now run it. If successful, the container should start, find the library, and exit cleanly.

docker run --rm dhi-monitoring-test

Output:

Node.js version: v24.11.0

dd-trace module loaded successfully!

Running as UID: 1000 GID: 1000

DHI customization test successful!

Success! We have a working application with a custom global library, running on a hardened, non-root base.

Security Check

We successfully customized the image. But did we compromise its security?

This is the most critical lesson of operationalizing DHI: hardened base images protect the OS, but they do not protect you from the code you add.Let’s verify our new image with Docker Scout.

docker scout cves dhi-monitoring-test --only-severity critical,high

Sample Output:

✗ Detected 1 vulnerable package with 1 vulnerability

...

0C 1H 0M 0L lodash.pick 4.4.0

pkg:npm/lodash.pick@4.4.0

✗ HIGH CVE-2020-8203 [Improperly Controlled Modification of Object Prototype Attributes]

This result is accurate and important. The base image (OS, OpenSSL, Node.js runtime) is still secure. However, the dd-trace library we just installed pulled in a dependency (lodash.pick) that contains a High severity vulnerability.

This proves that your verification pipeline works.

If we hadn’t scanned the custom image, we might have assumed we were safe because we used a “Hardened Image.” By using Docker Scout on the final artifact, we caught a supply chain vulnerability introduced by our customization.

Let’s check how much “bloat” we added compared to the clean base.

docker scout compare --to <your-org-namespace>/dhi-node:24.11-debian13-fips dhi-monitoring-test

You will see that the only added size corresponds to the dd-trace library (~5MB) and our application code. We didn’t accidentally inherit apt, curl, or the build caches from the builder stage. The attack surface remains minimized.

A Note on Provenance: Who Signs What?

In Part 2, we verified the SLSA Provenance and cryptographic signatures of Docker Hardened Images. This is crucial for establishing a trusted supply chain. When you customize an image, the question of who “owns” the signature becomes important.

- Docker Hub UI Customization: When you customize an image through the Docker Hub UI, Docker itself acts as the builder for your custom image. This means the resulting customized image inherits signed provenance and attestations directly from Docker’s build infrastructure. If the base DHI receives a security patch, Docker automatically rebuilds and re-signs your custom image, ensuring continuous trust. This is a significant advantage for platform teams creating “golden images.”

- Local Dockerfile: When you build a custom image using a multi-stage Dockerfile locally (as we did in our tutorial), you are the builder. Your docker build command produces a new image with a new digest. Consequently, the original DHI signature from Docker does not apply to your final custom image (because the bits have changed and you are the new builder).

However, the chain of trust is not entirely broken: - Base Layers: The underlying DHI layers within your custom image still retain their original Docker attestations.

- Custom Layer: Your organization is now the “builder” of the new layers.

For production deployments using the multi-stage build, you should integrate Cosign or Docker Content Trust into your CI/CD pipeline to sign your custom images. This closes the loop, allowing you to enforce policies like: “Only run images built by MyOrg, which are based on verified DHI images and have our internal signature.”

Measuring Your ROI: Questions for Your Team

As you conclude your Docker Hardened Images trial, it’s critical to quantify the value for your organization. Reflect on the concrete results from your migration and customization efforts using these questions:

- Vulnerability Reduction: How significantly did DHI impact your CVE counts? Compare the “before and after” vulnerability reports for your migrated services. What is the estimated security risk reduction?

- Engineering Effort: What was the actual engineering effort required to migrate an image to DHI? Consider the time saved on patching, vulnerability triage, and security reviews compared to managing traditional base images.

- Workflow: How well does DHI integrate into your team’s existing development and CI/CD workflows? Do developers find the customization patterns (Golden Image / Builder Pattern) practical and efficient? Is your team likely to adopt this long-term?

Compliance & Audit: Has DHI simplified your compliance reporting or audit processes due to its SLSA provenance and FIPS compliance? What is the impact on your regulatory burden?

Conclusion

Thanks for following through to the end! Over this 3-part blog series, you have moved from a simple trial to a fully operational workflow:

- Migration: You replaced a standard base image with DHI and saw immediate vulnerability reduction.

- Verification: You independently validated signatures, FIPS compliance, and SBOMs.

- Customization: You learned to extend DHI using the Hub UI (for auto-patching) or multi-stage builds, while checking for new vulnerabilities introduced by your own dependencies.

The lesson here is that the “Hardened” in Docker Hardened Images isn’t a magic shield but a clean foundation. By building on top of it, you ensure that your team spends time securing your application code, rather than fighting a never-ending battle against thousands of upstream vulnerabilities.